Shir Alon: This course was designed in answer to a very practical need – I had to teach a First Year Seminar and make it attractive to incoming freshmen with little knowledge (or specific interest) in the Middle East, in Arabic, or in literature, for that matter. The Arabic program at W&L is fairly new, and while it is growing fast (thanks to the relentless Antoine Edwards), it still needs to “make a name for itself” on campus. So to be honest, initially the djinn were a hook. It is only later that I realized what a productive frame this is for a broad-scope Arabic literature course, since it allowed us to draw connections between classical and modern texts without wasting too much time on facile questions of authenticity or imitation, which often dominate historical survey of modern Arabic literature.

Shir Alon: This course was designed in answer to a very practical need – I had to teach a First Year Seminar and make it attractive to incoming freshmen with little knowledge (or specific interest) in the Middle East, in Arabic, or in literature, for that matter. The Arabic program at W&L is fairly new, and while it is growing fast (thanks to the relentless Antoine Edwards), it still needs to “make a name for itself” on campus. So to be honest, initially the djinn were a hook. It is only later that I realized what a productive frame this is for a broad-scope Arabic literature course, since it allowed us to draw connections between classical and modern texts without wasting too much time on facile questions of authenticity or imitation, which often dominate historical survey of modern Arabic literature.

Secondly, this was an occasion for me to work through some questions I am dealing with in my own research. I write a lot about the politics of memory, and I was bothered by the manner “hauntology,” or ghosts and spirits, had become our most common metaphor for thinking about how the past exists in the present, or about how memory and trauma operate. Despite its appeal, I think there are some serious shortcomings to this model, in terms of the kind of political action it inspires. Djinn, however, are a different kind of supernatural entity. Unlike ghosts, they are not remnants of a past that we presume dead, but live lives parallel to ours. I had a sense that there is a different kind of politics to be gleaned here, particularly when djinn are evoked in modern works of literature and visual arts. I wanted to get a better sense of this genealogy, and the students were great for working through this together with me.

Finally, since this was a First Year Seminar, and therefore a first experience of working closely with texts for most students, I wanted to make sure they acquire tools to think of literary genres, forms, translation, or adaptation. The trope of the djinn could bring together an astonishing array of different modes of writing and storytelling.

Are most students relatively familiar-ish with djinn when they start the class? What sort of baggage do they have / not have around djinn vs. other courses that come together around Arab and Arabic literatures?

SA: The majority of the students have never heard of djinn, and it took them a while to connect whatever they have encountered in the past, such as Disney’s Aladdin, with this rich cultural tradition. I did have a number of Muslim students who had heard about djinn in their families, but they were not familiar with textual traditions associated with them.

In general, this was an astoundingly disenchanted and un-haunted group of students – at the beginning of the term I asked for stories, either personal or family tales, of encounters with the supernatural, and no one had anything to offer. I wonder if the answer to this question would change now, after we have spent twelve weeks talking about demons.

You call week one (the one that’s “haunted by Orientalism”) “I Dream of Jeannie.” What role does humor (and playfulness) play in course design?

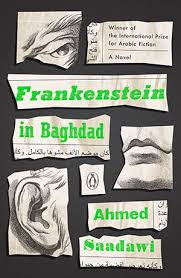

SA: Since the materials are so foreign to most of the students, it was important to find ways to make them accessible, and humor is probably the best. The world of the djinn, after all, is not just about horror or dread, but also about wit and goofiness. I wasn’t planning on it, but it quickly became clear that humor is one of the main theme we will deal with in this class, from Ibn Shuhaid’s The Treatise of Familiar Spirits and Demons, a biting satire of the literary scene of 11thcentury Cordova (in which two asses hold a poetry competition), through Emile Habibi’s brilliant use of humor as resilience and resistance in Palestine, to Ahmed Saadawi’s rewriting of Frankenstein as a dark satirical dystopia in Baghdad following the American invasion.

In this first class, we did watch clips from I Dream of Jeannie (the 1960s sitcom), alongside some medieval manuscript illustrations of djinn. The comparison, quite funny in itself, allowed me to introduce the topic of orientalist stereotypes in the Western media, and give out a general warning of our own orientalist prejudices when reading Middle Eastern literature. More importantly, it allowed us to start thinking about djinn as embodiments of social values, needs, or desires: contrasting, for example, the encyclopedic desire leading to the collection of nightmarish creatures in al-Isfahani’s Book of Wonders (14th c.) to the capitalist, wish-fulfilling, blond fantasy (in love with an astronaut! The very emblem of the wanderer to the limits of our world!) of the sitcom.

What work do Edward Lane and Mohamed Asad do in starting things off?

SA: Lane and Asad did a lot for us. The two excerpts we read appear as appendixes to Robert Lebling’s Legends of the Fire Spirits. Lane, rigorous Orientalist as he is, gave us a very helpful taxonomy of the different kinds of djinn we were to encounter in future readings. Asad, as a modern mu’tazili, gave us a sense of the effort to reconcile djinn, as they appear in the Quran, with modern rationalist or scientific thought. He creates an analogy between djinn and quantum particles, which exist even though we don’t have the technology or tools to witness their existence, except in extreme situations.

More importantly, reading the two texts together allowed us to reflect on the two writers’ preferences and shortcomings: Lane’s collapse of textual traditions, historical precedents, and the beliefs of his neighbors in Cairo into a typically Orientalist timeless mess, as well as Asad’s aversion to anything that could smell of “folklore” or “superstition” in favor of a rationalist model of religious experience.

I haven’t read Amira el-Zein’s Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn. Which poets are discussed, how does she approach the ways in which djinn inspired them, and how does this work into the course discussion & close reading of the texts?

SA: El-Zein’s study is useful as an archive, an overview of texts and anecdotes in which djinn play a role. She also (sometimes apologetically) reads the Islamic tradition against Western cultures’ supernatural traditions, so her chapter facilitated a discussion on the similarities between djinn and muses, and different ways of thinking about talent, inspiration, and the role of technical poetic skill. Her chapter made djinn seem like a very familiar notion, perhaps too familiar, according to some students. We read it together with Ibn Shuhaid’s The Treatise of Familiar Spirits and Demons, which necessitated an introduction to the particular value systems associated with classical Arabic poetry – so different from our own in terms of formal constraints, themes, and concepts of originality or plagiarism. El-Zein helped us realize that this book, beyond being a satire of poetic court culture, poking fun at Ibn Shuhaid’s contemporaries, was also a theoretical debate on these poetic values.

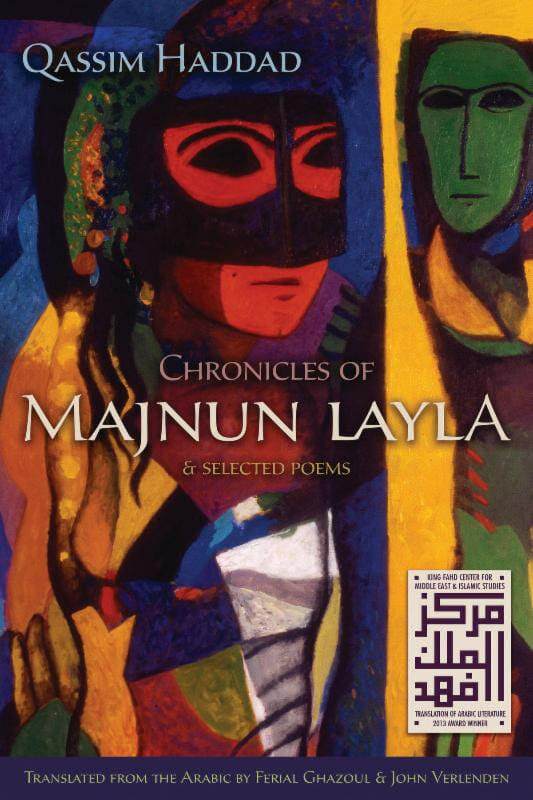

What does Majnun Layla open up, beyond djinnical transgression and romance?

SA: Majnun Layla provided the occasion to talk about adaptation, variation, and the “authorless” nature of folk stories. We started with some translations of poetry associated with Qays Ibn al-Mulawwah, the “original” Majnun, and continued with Nizami’s 12thcentury Persian adaptation. Then the students, working in groups, watched and analyzed modern adaptations of the story – from Ahmed Shawqi’s 1939 Egyptian operetta featuring Muhammad abd al-Wahab and Isfahan, through a number of Bollywood versions, to Habibi, a 2011 film based in Gaza, by the director Susan Youssef. Trying to account for this story’s lasting power, we discussed what persists between the different versions, and what changes. What is the minimum you need to keep Majnun Layla as Majnun Layla? What are the bare elements that make up this story, and what are the different ways people have used it? The story and various adaptations gave us plenty to talk about, such as irrational passion, madness and its sources, poetry as a container for these, and the choice to reject social values (including those of standard romance – in Nizami’s version nothing stops Majnun from marrying Layla except his own devotion to his devotion). The students also loved Nizami’s poetic language, which was something I did not expect.

SA: Majnun Layla provided the occasion to talk about adaptation, variation, and the “authorless” nature of folk stories. We started with some translations of poetry associated with Qays Ibn al-Mulawwah, the “original” Majnun, and continued with Nizami’s 12thcentury Persian adaptation. Then the students, working in groups, watched and analyzed modern adaptations of the story – from Ahmed Shawqi’s 1939 Egyptian operetta featuring Muhammad abd al-Wahab and Isfahan, through a number of Bollywood versions, to Habibi, a 2011 film based in Gaza, by the director Susan Youssef. Trying to account for this story’s lasting power, we discussed what persists between the different versions, and what changes. What is the minimum you need to keep Majnun Layla as Majnun Layla? What are the bare elements that make up this story, and what are the different ways people have used it? The story and various adaptations gave us plenty to talk about, such as irrational passion, madness and its sources, poetry as a container for these, and the choice to reject social values (including those of standard romance – in Nizami’s version nothing stops Majnun from marrying Layla except his own devotion to his devotion). The students also loved Nizami’s poetic language, which was something I did not expect.

What sort of discussions happen around the Thousand and One Nights (and their extended lives in other languages)? What are the students looking for, and finding?

SA: We had two sets of readings from Thousand and One Nights: the first included stories about the interactions between powerful djinn and witty, resourceful humans that can outsmart them. We explored the possibility that folktales, as stories that circulate orally and widely, contain knowledge or values relevant to a certain class. More specifically, we discussed the way power is represented in the stories, and the depiction of women, slaves, or the poor. The students were especially interested in the roles women play in these stories, and astutely noticed that, whether good or evil, women are always associated with sorcery – they have powers that cannot be quite controlled or understood…

Since we had talked extensively about adaptations when we covered Majnun Layla, we didn’t explore much of Alf Layla wa-Layla’s afterlives. I did take the occasion to assign a translation comparison exercise (the students compared passages from Burton’s 1885 translation with Haddawy’s 1990 translation). This is something I always try to incorporate in my classes since it is such an effective tool for honing close reading skills.

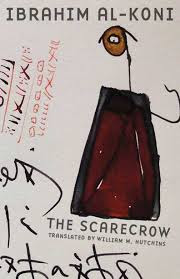

Ibrahim al-Koni is a wonderful place to go next. Why pair The Scarecrow with Freud?

SA: We had actually already started reading Freud’s essay “The Uncanny” together with “City of Brass” from A Thousand and One Nights, and it helped us identify classical and familiar elements of gothic horror, which appear already in that story (automatons, empty urban centers, sexy tempting specters). Then we used Freud as a bridge to al-Koni’s The Scarecrow, the first “modern” novel we discussed in the course. Freud suggests that we are overtaken by a sense of the “uncanny” when something familiar to us is suddenly defamiliarized, or more precisely, when we encounter something that reminds us of material we have repressed. For Freud, the repressed material is always primal fears and animistic worldviews, such as the sense that everything in the world is animated and connected to our own thoughts and consciousness.

I wanted the students to understand the idea of horror resulting from an encounter with repressed residues, or with things we have preferred not to deal with, since I think it is very fruitful. At the same time, I wanted them to realize how arrogant Freud is in this article (he goes a long way to emphasize that as a modern scientist who has overcome his primitive superstitions, he rarely feels the uncanny). This is where al-Koni comes in: he writes a world strange but similar enough to ours, in which Frued’s homocentric materialism – essentially the idea of an isolated individual operating in a dumb world – appears ridiculously and dangerously delusional.

What does Seraj Assi’s article about Emile Habibi and “collective autobiography” highlight about the context of Habibi’s writing, and what does it illuminate for student-readers about his choice to write about the supernatural? And “Gothic Palestine” is a very evocative title: What resonances are there to be drawn out between these different writers (Darwish, Zaqtan, Habibi) writing in different periods and different genres?

SA: In these two weeks we worked with a constellation of works by Palestinian writers and artists that in some ways evoke the supernatural or the spectral. Working through a trope, rather than using a geopolitical framework, allowed us to reflect on numerous manifestations of the fragmented Palestinian experience and its afterlives in various artistic genres. It helped us see continuities and connections as well as distinctions.

Emile Habibi’s Saraya The Ogre’s Daughter posits folktales as a shared cultural repertoire. Saraya, Habibi notes, is a figure from a Palestinian folktale, but also the name that the narrator gives to his childhood sweetheart, who presumably was expelled from Haifa in 1948. Habibi asks, at the beginning of this novel, who is the ogre and who is Saraya, and his constantly changing answers allowed us to talk about memory, betrayal, responsibility, and violence, and how the supernatural can act as a gateway to the past, of the individual and of the community. Assi’s article gave us crucial historical background on the “paradoxical” condition, as he calls it, of Habibi as Palestinian citizen of Israel. His notion of “collective autobiography” is useful not only to understand why Habibi integrates folktales, myth, and fantastic symbolic events into his personal memoire, but also why he uses so many voices in this text, jumping from first person to third person narration – thinking of the story simultaneously as the story of an individual and the story of a community solves many confusions.

Taking off from there, we started noticing how ghosts (as the past that lingers in the present, or the dead that is still among the living) are evoked in Palestinian poetry. In Memory for Forgetfulness, for example, Mahmud Darwish seems to suggest that the state of siege is equivalent to death in life. There is a wonderful scene in which the ghost of Izzedine Kalak makes a visit, only to un-emphatically insist that the next world is just like this one. But this is not a consistent position – in other poems, such as “They Didn’t Ask: What’s After Death,” the poet asserts the resilience of the Palestinian voice, still living despite the conviction (of the historian, of the artist, of the military general) of its extinction. For Zaqtan, on the other hand, ghosts and history are a matter of personal, daily grief – he never makes an appeal to the mythical metaphysics that are so characteristic of Darwish (all of these, by the way, we read in Fady Joudah’s evocative translations).

We also watched two video works in this unit: Sharif Wakad’s clever “To Be Continued…” in which the students could identify the use of A Thousand and One Nights, as Shehrazade is replaced by suicide bomber eternally postponing his own death; and a documentation of “The Ghost of Manshia,” a project by Israeli artist Ronen Eidelman, which spurred a discussion on the ghosts haunting perpetrators, and the relationship between guilt and trauma.

There was certainly something confusing about negotiating so many things together at once, but I think occasional confusion in the classroom is productive: it inspires questions rather than answers.

I certainly remember the personal ghosts from Radwa’s Atyaf / Spectres, but I don’t think I remember the supernatural? Why include Radwa’s book?

SA: It’s funny, but before this question I never even considered this to be a course about the supernatural. I was primarily interested in the way djinn are evoked in modern works of literature to perform all sorts of new labor, in our world rather than in a parallel one. Since we talked about the meaning of telling Palestinian history as a ghost story in the previous week, Spectres was the natural place to go (Shagar, the character that Radwa writes in this novel, is a historian writing a book about the Deir Yassin massacre called The Spectres). The novel led to a lot of very productive arguments on historiography, narrative, and the difference between history and literature, beyond a simple fact/fiction binary (Haydn White’s death coincided with that class, and his ghost definitely accompanied us).

There is also an interesting conversation in Spectres on the qarina, or one’s double among the djinn, associating it with the ancient Egyptian Ka. It led us to a debate about the various practical uses of having a double (in life or in fiction).

And Frankenstein in Baghdad does all sorts of interesting things with the supernatural, in a violent crossover between traditions. What particular things are students reading for, finding, talking back around, making connections to?

SA: It is really tempting to read Frankenstein in Baghdad as a one-to-one allegory for the American invasion and the ensuing violence that destroyed Baghdad. Who does the whatsitname stand for? How does the breakup among his followers satirize the sectarian divisions among the opposition forces? The students are drawn to these readings because, among other things, they want to understand these very recent events, in which they too are implicated, and they hope that the novel will give them this knowledge. This doesn’t work, of course. I try to give them enough background to understand the novel, but eventually I focus on questions of genre, and the manner Saadawi mixes different genres together to present a particular take on the war.

SA: It is really tempting to read Frankenstein in Baghdad as a one-to-one allegory for the American invasion and the ensuing violence that destroyed Baghdad. Who does the whatsitname stand for? How does the breakup among his followers satirize the sectarian divisions among the opposition forces? The students are drawn to these readings because, among other things, they want to understand these very recent events, in which they too are implicated, and they hope that the novel will give them this knowledge. This doesn’t work, of course. I try to give them enough background to understand the novel, but eventually I focus on questions of genre, and the manner Saadawi mixes different genres together to present a particular take on the war.

Many of the students had read Frankenstein in high school, and therefore are able to make a lot of observations about the way Frankenstein in Baghdad diverges from the original, using the trope of the animated corpse to different ends. In general, they reacted to the novel more empathically than I expected. I found this to be so interesting! Reading the novel, I was primarily interested in the absurd depictions of the hapless Tracking and Pursuit Unit, whereas the students were invested in the fate of the characters (Hadi, Elishva, and even the whatsitname) and the manner they evoke sympathy. My suggestion that this is a work of satire, full of (absurd, cynical, morbid) humor, was met with a lot of resistance – the students didn’t think it was funny at all.

Reading the novel as detective fiction went over much better. We used G. K. Chesterton’s essay “How to Write a Detective Story,” to identify how Saadawi uses some elements of the classic genre only to mess them up.

I’m not familiar with the film Under the Shadows. Why this film, and why with Frankenstein in Baghdad?

SA: Under the Shadows is a terrifying horror film taking place in Tehran during the Iraq-Iran war. It diverges from our Arabic focus, but is grounded in the same Islamicate tradition of djinn we have been discussing for a while, so the tropes were largely familiar. At the same time, the film belongs squarely in the Hollywood psychological horror genre, so it fit perfectly with the previous class’s discussion of genre fiction and its ability to shape and distort expectations. Like Frankenstein in Baghdad, Under the Shadows uses djinn to elaborate on the effects of fear during war, but it also smartly evokes life in Iran shortly after the revolution, and (most horrifying for me) unspoken fears surrounding the experience of motherhood.

Why end on the wonderful, teeming supernatural worlds of Alif the Unseen (which was published before Frankenstein)? What sort of jumping-off points & open-ended questions does it offer?

SA: I wish we had more time to discuss Alif the Unseen! We end there partly because I knew we wouldn’t have time to read through all of it, but it is such a thrilling read so I can hope that some students will finish it on their own.

It is also an incredibly fun text to conclude with, since it evokes so many things we have discussed over the quarter. In some sense this novel brings us back full circle, to the beginning of the course: after a whole semester discussing djinn as a means to talk about other things – poetic inspiration, irrational desires, fears of death and violence, memory – we end with a text that insists, very attractively, that the djinn live by us, and not just for us to figure out our issues through them. It reopens the question of unseen and unimaginable things that might be just behind the corner. And it is also always better to end the semester with a revolution rather than with war.

Are there books or texts you would remove or add when doing this class again? Moments you’d like to revise or expand?

SA: Coming now to the end of the semester, I realize I would have liked to have dedicated more time to manuscripts of the occult and to folklore (for lack of a better name) – to the way people actually live their lives with the djinn, not just to their literary presence and symbolic potential. My own comfort zone as a literary scholar is clear, but if I teach this course again I think I would definitely need to step out of it.

#

Schedule for ‘Djinn Stories: Poetry, Madness, and Memory’

Week 1: I Dream of Jeannie

T: Introduction to course themes: Haunted by Orientalism

- Short introductory texts: Edward Lane (1836) , Muhammad Asad (1980)

- In class: Visual Representations, from Al-Isfahani to Christina Aguilera

R: Jinns in the Quran:

- Sūrat al-Raḥman; Sūrat al-Jinn

Optional: Mark Allen Peterson, “From Jinn to Genies: Intertextuality, Media, and the Making of Global Folklore.”

Week 2: Poets and their Jinn

- Abu Amir ibn Shuhaid, The Treatise of Familiar Spirits and Demons (Risalat at-tawabi wa z-zawabi) (al-Andalus, 1025), pp. 59-96 (the “Introductory Essay” is optional).

- Amira El-Zein, “Djinns Inspiring Poets,” from Islam, Arabs and the Intelligent world of the Jinn (2009).

- In Class: Taʾabaṭa Sharran, “How I Met the Ghoul” (Qit’a nuniyya, 6th)

Week 3: Majnun and Love’s Demons

- Poetry excerpts from Qays Ibn al-Mulawwah (two translations)

- Nizami, The Story of Layla and Majnun (Persian, 1188)

- In class group work: Cinematic adaptations of Majnun Layla, from Cairo to Bollywood.

- Optional: Qassim Haddad, Chronicles of Majnun Layla (Poetry, Bahrain 1996)

Week 4: Jinn and Humans

- Excerpts from One Thousand and One Nights

- Tale of Merchant and the Jinni

- Tales of the Three Sheikhs

- City of Brass

Week 5: Demonic Power

- Ibrahim al-Kouni, The Scarecrow (Libya, 1998, 128pp.).

- Freud, “The Uncanny” (1919).

Week 6: Folktales and Loss

- Emile Habibi, Saraya The Ogre’s Daughter (Palestine, 1991) pp. 13-56.

- Seraje Assi, “Memory, Myth and the Military Government: Emile Habibi’s Collective Autobiography,” Jerusalem Quarterly 52 (Winter 2013): 87-97.

Week 7: Gothic Palestine

- Emile Habibi, “The Odds and Ends Woman” (1968)

- Poetry selections from Mahmud Darwish and Ghassan Zaqtan

- Excerpt from Darwish, Memory for Forgetfulness

- Celia Rothenberg, “My Wife is from the Jinn: Palestinian Men, Diaspora, and Love,” from Islamic Masculinities (2006).

- In Class: Video art, Sharif Wakad, “To Be Continued…”; Ronen Eidelman, The Ghost of Manshia

- Optional: Anna Ball, “Communing with Darwish’s Ghosts: Absent Presence in Dialogue with the Palestinian Moving Image,” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 7:2, (2014): 135 – 151.

Week 8: Personal Ghosts

- Radwa Ashour, Specters (Egypt, 1992, 200pg).

Week 9: Hauntings – Horror and Rewritings

- Ahmed Saadawi, Frankenstein in Baghdad (Iraq, 2013, 280pp.).

Week 10: Horror Continued (Mar 20; 22)

- (Saadawi continued)

- Babak Anvari, Under the Shadows (film, Tehran 2016).

Week 11: Jinn of the Cyber World

- G Willow Wilson, Alif the Unseen (Fantasy/Cyber punk, US/Cairo, 2012, 400pg).

Shir Alon got her PhD in Comparative Literature from UCLA, where she also taught classes on “Orientalism in Hebrew Literature” and “Nomadism and Migration in Middle Eastern Literatures.” She is currently a Mellon Junior Faculty Fellow in Arabic Literature at Washington and Lee University. Her research focuses on modern Arabic and Hebrew literatures, legacies of Orientalism, transnational modernisms, and affect theory.

Shir Alon got her PhD in Comparative Literature from UCLA, where she also taught classes on “Orientalism in Hebrew Literature” and “Nomadism and Migration in Middle Eastern Literatures.” She is currently a Mellon Junior Faculty Fellow in Arabic Literature at Washington and Lee University. Her research focuses on modern Arabic and Hebrew literatures, legacies of Orientalism, transnational modernisms, and affect theory.

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

No strings attached Hoookupyou keen?