Sam Shepard, Writer — Homage

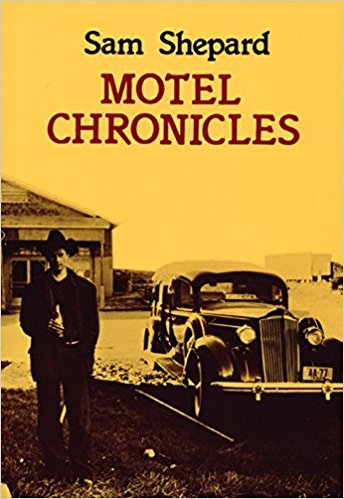

My translation into French of Motel Chronicles (and Hawk Moon) came out in 1985 & reused the same cover photo than the US edition above, though I had the original photo, much wider, and wrote the introduction below (in French, originally, quickly translated it right now) based on that one, having asked the publisher, Christian Bourgeois to do a wrap around cover image — unhappily the French edition cropped the shot even further than the City Lights edition did, so that most of what I speak about is no longer visible. Still, this morning, the day after we learned of Sam’s passing, here is that intro as my homage to his writing:

SAM SHEPARD, WRITER

Sam Shepard is a writer. Before all else. The rest is dream. American dream, of course. Look at the cover photo. It could be shot from a John Ford movie: a man standing besides a car. Behind him, a house, half wood, half brick: with no more permanence than the man or the car. Nearly as mobile as the trailer truck back right, the american dwelling par excellence: a box of corrugated metal siding on wheels. And behind the car, the road, or rather, a crossroads, a choice. The car isn’t just any car: a superb fifties model, but also, if you move in close enough, a hearse: the words “Funeral Coach” are readable on the windshield.

The man standing next to the car is Sam Shepard, the author. In his hand, a bottle of coke, on his head a cowboy hat. It is rare to find pictures of an author, standing tall, visible from head to toe. But in this case the photo is the right one, exactly. The author in his element. There, where he writes, what he writes. Not behind a desk. Not a close-up profile shot. No well-stacked book shelves, that sort of corporate backdrop that reassures author and reader, clog the horizon. No, what you see here is the American author, par excellence. In his element: space.

For if European literature has since always been obsessed with time, American literature has essentially been preoccupied with space. In his essay on Melville, Call me Ishmael, the poet Charles Olson, spelled SPACE in capital letters “because it comes large here,” and because he takes it “to be the central fact to man born in America, from Folsom cave to now.” All of American literature inscribes itself in that obsession: it has been, it is, and will most likely remain a literature of space. Its imagination is geographic. Its proustian madeleine is an Impala 1958.

Despite all the criticism one can throw at it, the Western remains the truest image of America. Since long before cinema and over a space that defies the effects of fashion. From James Fenimore Cooper’s The Prairie to William Eastlake’s Portrait of an Artist with Twenty-Six Horses, what is most deeply American comes through those spaces. Even when the horses are supplanted by rockets: space is and remains the final frontier. There’s thus nothing strange in discovering Sam Shepard as Chuck Yaeger in The Right Stuff, a movie that speaks of the conquest of space.

If for a European literary sensibility the fact of Shepard’s media superstar status, more like that of a rock star, may seem strange and even “not serious,” this isn’t so in the American space. But let’s quickly sum up Shepard’s career: born in 1943 inFort Sheridan, Ill., he spent the major art of his south in the rural areas of Southern California. In on of his rare interviews he says that he grew up in “a car culture for adolescents” and attributes a sort of “cheap magic” to those southern Californian towns.

Like all those of his generation, he dreamed of becoming as major rock star. Meanwhile he wrote plays, about forty until now, one of which — La Turista — won an Obie in 1967 and another — Buried Child — was the first off-Broadway play to win a Pulitzer, the highest literary award in the U.S. He also worked on the scenario of Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point and more recently he wrote Paris, Texas for Wim Wenders.

Motel Chronicles is his second book of proses. It is made up of fragments, autobiographical sketches that speak of his mother, his father, his friends, people met by chance in motels along the road. The prose is fast and lean, even frugal. It is the opposite of his writing for the theater, which often tends toward verbal delirium and near surrealist effects. It is also at the opposite of Kerouac’s writing, that Eastern romantic who came to dream “on the woad” in the West.

The road, the cars, Sheppard knows them, since his earliest childhood: “… my mother gave me ice cubes wrapped in napkins to suck on. I was teething then and the ice numbed my gums… That night we crossed the badlands, I rode on the shelf behind the back seat of the Plymouth and stared out at the stars.” He never stopped traveling, even if at moments the desire came to stop, to settle down. In his truck, years later, with his mother and his son, he watches a car glide through the Napa Valley pastureland: “The red Impala disappears behind a hedgerow of Giant Blue Gum Eucalyptus. The pasture is soaked in rain. I don’t feel like moving much. I’d just as soon live in this truck. I’d just as soon let the grass grow right through the tires.”

But of course he keeps going: that part of America is made for moving, not for stopping. It is by the way on the road, while driving, that narrative takes shape. Two men, two friends, in a truck, after having driven for thirty-two hours straight: “A certain crazy state of mind started to take hold of the two men. They passed through the territory of inner complaining about not having enough sleep and went straight into a kind of ecstatic trance. Their bodies gave up the ghost and they began to tell stories, mixing the past and present at random.”

Those are the stories Motel Chronicles tells. And as Jack Gilbert, another great American playwright, said: “ Sam Shepard is a shaman — a New World shaman. Sam is as American as peyotl, sacred mushrooms, rock and roll…” Let me only add that Shepard is also a great writer.

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux