Nomadic Nomadics

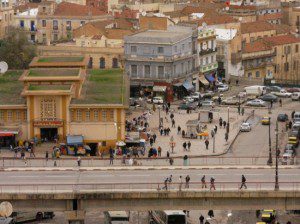

Arrived in Mostaganem, Algeria tonight for a 2 day conference on translation organized by the Amazigh (i.e. Berber) High Authority at the University here. Thus, with apologies, no postings for the last 3 days as I was traveling from NYC to Luxembourg via Amsterdam for 24 hours in the bosom of the family, then on to Paris for a night at friends & the plane to Oran this afternoon (yesterday afternoon, i.e. Sunday, as now it is 12.20 a.m. here).

Mosta happens to be the birth city of the poet Habib Tengour, who will join me here tomorrow for our round-table on translating the Maghreb on Tuesday. More on all of that as things happen. While here, I’ll also go over some of Tengour’s work I’ve translated — & will serialize a short story from his book People of Mosta over the next 3 days. Here’s the opening:

Habib Tengour

Ulysses among the Fundamentalists

He had opened the newspaper directly to the cultural page, the only section whose meager columns he liked to skim through. He found the national press to be a most distressing read; on top of which the ink used dirtied your fingers. He cried out when he saw the photo, put his trembling hand against his forehead. Putting the paper down on a clean corner of the table, he leaned over it to read the small inset signed APS. Silvana Mangano had died, the old one. His hurried reading yielded only this terrible bit of information which instantly plunged him into an abyss of melancholia. She — so beautiful to look at! “She is dead!” he mumbled…

There, amidst the chipped cup half full of dirty coffee in a ray of sunshine, surrounded by breadcrumbs, splatters of jam and the newspaper to the side, he couldn’t imagine — he was as if anesthetized — the death of the actress. Could she disappear just like that? Without any supervening catastrophe upsetting the order of the day? The earth didn’t open up. He looked around as if to make sure of it. The restaurant room seemed normal. The customers were quietly eating their breakfasts. He distractedly thought about the Americans who had bombs with double timing: they exploded above their targets forming a heavy cloud that could stay in place, remaining immobile for several days. A laser ray in the middle of the cloud triggered a reaction that permitted in a fraction of a second to suck up all the oxygen of the circumscribed space, snuffing all animal or vegetable life. They were being experimented. The scientists claimed that the programming was infallible. Destiny? Unlucky star? He expected no relief from the tears or the blood or the disguised voices…

The photo was a bad reproduction of a shot from Bitter Rice. Hmida had informed the gang of the meaning of the title: “Rice is like love, it is life itself; and the life of the poor ain’t no cake.” He pretended that bitterness was the salt of life. The women were laboring like the men to survive because the condition of the peasantry was so harsh. But there was Silvana Mangano! She was curvaceous and knew how to tantalize. They were all drooling, eyes fixed on the movie screen, even Dadi who was finishing the sixtieth section of the Quran and who was cutting cheikh Adda’s classes to hang out with them. Benchâa, who was still going to the hammam with his mother, swore that he had seen Silvana Mangano’s double and that he had brushed against her loincloth in the hot room.

His eyes wandered over the photo at great length while he stuttered vague mumblings. As his eyes managed to distinguish her, she brought back the excessive sensations of childhood. Despair and enthusiasm commingled as a strange stirring grew in his belly. The first pallid awakenings to the body’s dampness, the excruciating cliché of the lost paradise, back there, at the seashore. The fearful parents forbade them to go swimming as long the marine genies had not slacked their ritual pedophile appetites by swallowing in jubilation the seven ritual victims of summer, in full view of the town’s citizenry. “The sea is a carnivorous labyrinth,” they would say. The Hamdawa brotherhood would sacrifice a black bull garlanded with red cloth and kauri shells; they would daub the reefs of Kharrouba with the still warm blood to entice those people.

Hmida had paid cash. Fifty douros to the gimp, the cashier at the Cinélux, to buy the photo of the actress in black stockings reclining on a barracks’ bed. Has this unforgettable pose forever determined my erotic fantasies? How many times, strolling along a boulevard or down the alleys of some park, haven’t I inadvertently stumbled across this memory!

The purchase of the photo had been quite an affair. Hmida was gifted for this kind of transaction! He made his money back in less than a week and earned some more on top of it, by making everyone shell out one douro for the right to keep it in one’s hands for three minutes behind the Bigord Mill. He was very careful that nobody should dirty the picture. Wewere fighting over our turns. A true potlatch among our gang… Finally, after many pleas and entreaties sweetened with assorted bits of karantika or paper cones of chick peas with cumin, he accepted to sell it to me for one Blek le Roc and one Rodéo comic book only after his business had started to fall off.

Hmida was the only one of our gang who had seen Ulysses with Kirk Douglas in the lead role, in Oran. That was after he had been released on probation from the juvenile detention center. His uncle had taken him to the Murdjadjo, an air-conditioned cinema with bar — his enticing descriptions of the place would leave us glum —, after he had promised that he would not filching or running away and that he would study hard because the country would need educated people. He agreed to tell us the story of the movie, interlaced with his personal adventures, many of which were invented, evenings after school, against payment of a sandwich or a créponé or a contribution toward a movie ticket.

He told himself under his breath that nothing would be the same as before. That that period had been blessed and beautiful, all in all, a period of happiness. Yes, happiness! Despite the implacability of colonialism! What did that mean? A cumbersome steretype. A part of his family had been decimated by the paras during Operation Binoculars. His father had spent his youth in jail; he had been tortured. He had embarked clandestinely for marseilles to escape capital punishment. He had settled in Nantes where he had found a job in a factory. After three months he gave up any idea of returning to Morocco. That’s when he enrolled in a center for vocational training to learn a trade and started to organize the first FLN networks. Condemned to death by the MNA, he moved to paris. His old friend from the PPA, Si Zitouni, who had stayed faithful to Messali, had warned him in time. A short time later Si Zitouni was executed. His father dropped politics and had his family join him.(to be continued)

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Thanks Pierre – this is great.

Bonjour from me to Habib – one of these days I’ll get back up to your hemisphere and visit Habib again and meet you in person

Enjoy the conference

Every best wish,

Pam

I am sure you get many of these but……don’t forget the postcard !