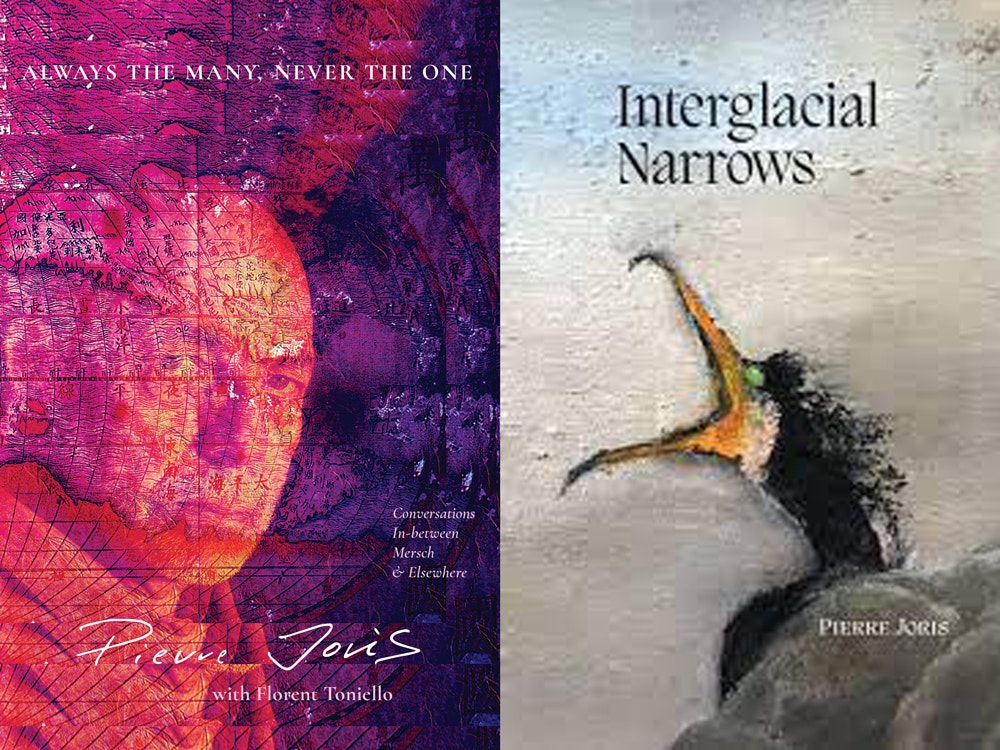

Jason Weiss’ Brooklyn Rail review of “Interglacial Narrows” & “Always the Many, Never the One”

Interglacial Narrows

(Contra Mundum Press, 2023)

Always the Many, Never the One

(Contra Mundum Press, 2023)

In his book of conversations Always the Many, Never the One, Pierre Joris notes that he likes to date his arrival in New York, in 1967, as being “three months after John Coltrane passed.” For a lad who had already left his native Luxembourg to go study medicine in Paris, where he discovered that poetry was his calling instead, the shift in direction could not be clearer. Coming from a multilingual environment, he had no trouble deciding which would be his language for writing—his fourth, in fact: English. He had first heard Charlie Parker while still in high school, when he was also picking up on the energy of the Beats, so he moved to the States and plunged into the new American poetry. By the end of that decade, under Robert Kelly’s guidance at Bard College, he began to translate Paul Celan’s poetry into English, a commitment that was to last him more than fifty years.

That early awakening to poetry brought with it yet other paths. After dropping out of medical school in Paris, Joris stayed for a while in a room upstairs at Shakespeare & Company bookshop and there his roommate was Moroccan poet Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine, who introduced him to the new North African writing. Many literary friendships, exchanges, and translations ensued through his contact with Maghrebi writers and the wider Arab world. During the 1970s and ’80s, he wandered back to earlier terrain: further studies in London, teaching at the University of Constantine in Algeria, doing radio and translating in Paris (mostly into French, for the publisher Christian Bourgois, including Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues and Sam Shepard’s first two books of prose), eventually returning to settle and teach in the US. With Jerome Rothenberg, he edited the two initial volumes (1995, 1998) of the monumental Poems for the Millennium series, with its worldwide range of modern and postmodern poetry, and then they brought out large editions of poetry by Pablo Picasso and Kurt Schwitters in translation. Joris was well prepared, therefore, by the time he co-edited the equally innovative (& massive) fourth volume of Poems for the Millennium, with Algerian poet Habib Tengour, The University of California Book of North African Literature (2012). His essays on modern Arabic writing, Arabia (not so) Deserta (2019), partly an outgrowth of that project, offered another bridge to anglophone readers.

Thus to tell something of the rhythms Joris carries in his ear. After many previous collections, Interglacial Narrows gathers poems written between 2015 and 2021, organized into four sections that provide less a unified sequence than distinct territories of focus, with plenty of overlap and shared concerns. The first section, “Loess and Found,” would seem the baggiest, except it begins and ends with poems in memory of longtime poet friends newly departed. The two pieces couldn’t be more different, in language and line, yet both call up the person in mind with a loving specificity in music and tone. “Elegy for Anselm Hollo” delights in the resonances of words and small phrases, how they can yield unexpected transformations, with a subtle underlying humor:

a thousand

crows

on the snow

& yet, 2 crows

already make a crowd.

A moment later, he pivots in an ancient gesture of camaraderie toward his fellow transplant from across the sea:

& yet,

we have to travel, Anselm

because there are wines

that don’t.

By contrast, “A Three-Minute Composition à la Mode Dalachinsky to Celebrate Steve” embraces at full throttle the long swinging lines of the beloved talkaholic and nonstop poet from Brooklyn, recounting rambles through the East Village:

you hadn’t seen me yet

so I took out my phone

shifted coffee bags under left arm

& snapped you & Yuko eating

(see, here is the photo

I’m not making this up, then you saw

& said Hi Bub

With his substantial experience as a translator and the agility gained, in addition to his early start navigating several languages and literatures, Joris in his poetic voice seems ever protean, eluding a fixed style. Rather, the circumstances of the poems elicit their own language and processes according to the particular dialogues that animate them. The third section of the book, “Homage to P.C.,” in that sense, shows the remarkable range of poetic tonalities he employs while wrestling with the difficult angel, as it were. But that is also because this set breaches the general time scheme of the book by taking in all his poems related to Celan, reaching back to 1969, granting a glimpse of Joris’s broader poetic practice. The last was written in 2020, a year that marked the hundredth anniversary of the poet’s birth and the fiftieth of his death, and crucially for Joris the publication of the final volumes of his Celan translations: Memory Rose into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry (his versions of the collected later poems appeared previously) and Microliths They Are, Little Stones: Posthumous Prose.

Among the late poems in the Celan-orbiting group, Joris touches down on familiar ground, where he lands again and again throughout the book: in the here and now of where he lives, and has for the past two decades, in Bay Ridge, at the southwest corner of Brooklyn, especially the view from his desk or on his morning walks along the Verrazano Narrows, as in the book’s title. “Earlier Today I Saw” tells of “an old atlas / floating down” the Narrows, but then an odd footnote found that same day recalls Celan and his suicide, and the connection becomes apparent as the poem casts both image and reflection of him “floating down / the Seine, // for so many years, / my Atlas.” Indeed, the Narrows, the shore, the waters, the distances, the full implications of that location, enter the poems often. The penultimate poem in the first section, “Shipping Out at 1:25 P. M. on Herman Melville’s 200 Birthday,” simply lists the evocative names, destinations, and speeds of nineteen ships passing through that stretch of the harbor. His attentions to that local realm take up the entire second section, “The Book of U,” which first appeared as a bilingual chapbook published in Luxembourg, in collaboration with his wife, multimedia artist Nicole Peyrafitte, whose painting of the bright, curved, wide-open beak of a cormorant graces the cover. In this set, the cormorants draw the poet’s eye as much by their nature and habits on that shore as by where they take him in thought as guide or spirit. Always on the lookout for their company during his walks, he thinks of them as “my cormorants,” until one day he doesn’t see any and concludes:

the only one

of my birds

left

— is me

& I worry

that I may be

more rant

than

core.

In the restless mosaic of reflections and poetic fragments that make up the book’s final section, “Up to & Including the Virus,” an intermittent daybook, Joris returns to the local as evidence of some greater trouble, in the late winter of that fateful year: “Meanwhile outside there are fewer cars and people. […] Things look semi-normal, but I feel odd.” A month later, almost like a tarot card come to life, a hanged man turns up in the Narrows Botanical Garden across the street. Amid such strange intimations of mortality, he seeks out signs of spring in the budding branches, and when he does venture out from sheltering at home, a heightened instinct for birdwatching proves a salve and confirmation that life somehow goes on. Sightings of a kingfisher bring to mind Charles Olson’s kingfisher poem, and repeatedly glimpses of the outer world in these disordered times call forth dreams and recollections of friends, family, literary forebears. Diligence in washing his hands reminds him of his surgeon father’s handwashing, which leads to thoughts of his grandfather who died before Joris was born, though most mornings gazing out his window he greets “grandfather Joseph who just before or right after 1900 came up these Narrows in a Conradian ship sailing into New York Harbor.” The mixing of poetic registers reflects his affinity for “porous borders,” between literary forms as between languages, cultures, countries. Inevitably, these writings approach a kind of closure with his note on receiving a second booster shot of the COVID vaccine at the moment of the winter solstice, while looking toward “the sun as it / moves & grows & makes / more light day by day.” But his last entry opens the book out yet again as it takes up a question from the other work being completed at that time, Always the Many, Never the One, in offering a further comment about his “practice of the in-between.”

A few years prior, Joris took part in a series of events that celebrated the Syrian poet Adonis and which culminated in a book attributed to both: Conversations in the Pyrenees (2018). That hybrid form, between essay and interview, oral and written, attracted him as an opportunity to explore thoughts on poetry, language, cultural politics, science, in the context of his own long itinerary as nomadic poet and translator, so he invited the Luxembourg-based writer Florent Toniello to be his questioner in those exchanges, which took place during the latter half of 2021. Like the multiple strands of the poetry, Always the Many unfolds a marvelous concatenation of themes that are by turns personal, artistic, and conceptual, often all at once. Here the books and writers enter into his life from the ground up. He first got interested in America from boyhood reading of the German romantic novelist Karl May and his tales of the Old West, notably the vivid, completely invented Native American characters. Through the eight conversations, different notions of the West keep cropping up: whether in speaking of the Maghreb, the west of the Arab world, or the mythical West as played with in numerous works, such as Edward Dorn’s Gunslinger, which he brings up appreciatively while discussing achievements in the long poem over the past fifty years. On the other hand, when Joris first arrived at Bard and asked Robert Kelly what he should do to improve his (American) English, Kelly told him to listen to baseball broadcasts on the radio. These are hardly mere anecdotes, rather they indicate a whole web of relationships.

In elaborating a discourse of the in-between along the numerous paths of this book, especially in the final conversation, Joris pulls together an impressive array of threads. Already poised by the circumstances of his upbringing for a role as intermediary from one culture to another, confirmed by his work as a translator, he recognized early on that the open field poetics of Olson, Duncan, and others, was a helpful way to think about his own practice as a poet. There he could remain alert to all kinds of information that might enter the poem, by chance or by purpose, and “that doubleness of the known & the unknown […] opens another in-between-ness, inside of which you have not just to be active & work, but you also have to be passive & listen & respond.” But more than a perspective for poetry, that is “where we are” in our existence. “We don’t see that the world is continuously changing & moving, so that you’re always in an in-between.” He traces such multidirectional thinking back at least to the Sufi poet Ibn Arabi who saw the notion of the barzakh—a liminal space comparable to the Bardo or Purgatory—as reflective of life itself; and he finds similar ideas today all over the place, in various scientific works and from other cultural angles, like Edouard Glissant’s relational poetics and Gloria Anzaldúa’s use of the concept of Nepantla. Such is the pleasure of these conversations that they keep sparking new connections to follow long after the book falls silent.

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux