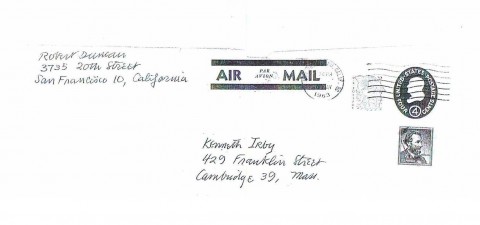

Robert Duncan to Kenneth Irby, May 10, 1963

Last year as he & his work were being celebrated at the University of Lawrence, Kansas [see post here] Ken Irby gave me a copy of & permission to reprint the following letter by Robert Duncan — the first one Irby received from RD. It took awhile, but here it is finally, as photo repro & in a transcription. (The few words that were unreadable are in bold with a question mark after them).

Last year as he & his work were being celebrated at the University of Lawrence, Kansas [see post here] Ken Irby gave me a copy of & permission to reprint the following letter by Robert Duncan — the first one Irby received from RD. It took awhile, but here it is finally, as photo repro & in a transcription. (The few words that were unreadable are in bold with a question mark after them).

May 10, 1963

Dear Kenneth Irby, No, I don’t mind your writing to me, and it’s got be “out of the blue” at some point. Ron Loewinsohn had calld my attention to your poem in change when he brought me my copy, and I like then immediately how solid (vs. fluid) words and sentences, in the movement of the poem the rise, are for you. By contrast to my own rhetorical river-of-sound nature that has to exert some vigorous art to give substance to the immediate area of the poem. And now that I read these two poems (the one you sent me with the letter) the land, Kansas, and plain begin to be a language — you’ve not really to win your way thru to writing at all (as I had some six years of writing poetry all wrong, before in 1942 some glimmer of a natural voice appeard — and then another four before, with Medieval Scenes, I began to have a poetic, an idea of what had to be done, and another two years (the Venice Poem) before I could do what I knew had to be done.)

All your questions — of starting the poem; of where does the poem work beyond us, beyond its own; — but then you see that even as you ask me — are urgencies of a poetic forming in you. I can tell you at least of my own experience that these questions will never be done. I am dependent upon the poem itself and must follow it like a trail thru a jungle that exists (the trail) only in the immediate stop [?] on takes — all other appearances of trail, far ahead or just behind the explorer (who must after all map the territory as he goes, in order to go), all other sights of the way being false to the country.

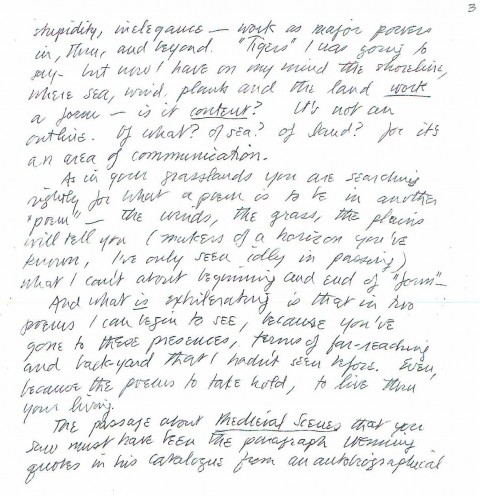

Every mastery and obedience in the poem, the way we respect the syllable, the word — demand every feat of it — the firmness with which we intend our formal feeling — of outline, of mass, of phase, of parts belonging [?] to a whole — does work beyond us and the poem. For we and the poem too have been workd in our effort. I mean here just in the sense that every act works “beyond” — of any man. Ignorance, affectation, “weakness”, stupidity, inelegance — work as major powers in, thru, and beyond. “Tigers” I was going to say- but now I have on my mind the shoreline, where sea, wind, plants and the land work a form — is it content? It’s not an outline. Of what? of sea? of land? For it’s an area of communication.

As in your grasslands you are searching rightly for what a poem is to be in another “poem” — the winds, the grass, the plains will tell you (makers of a horizon you’ve known, I’ve only seen idly in passing) what I can’t about beginning and end of “form” —

And what is exhilerating is that in two poems I can begin to see, because you’ve gone to these presences, terms [?] of far-reaching and back-yard that I hadn’t seen before. Even, because the poems do take hold, do live thru your living.

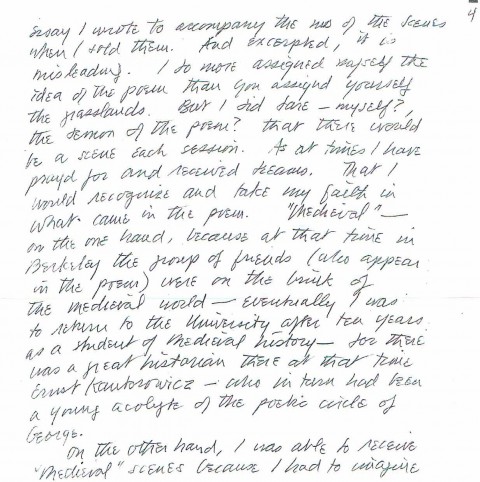

The passage about Medieval Scenes that you saw must have been the paragraph ueming [?] quotes in his catalogus from an autobiographical essay I wrote to accompany the ms of the scenes when I sold them. And excerpted, it is misleading. I do more assigned myself the idea of the poem than you assignd yourself the grasslands. But I did dare — myself?, the demon of the poem? That there would be a scene each session. As at times I have prayd for and received dreams. That I would recognize and take my faith in what came in the poem. “Medieval”— on the one hand, because at that time in Berkeley the group of friends (who appear in the poem) were on the brink of the medieval world — eventually I was to return to the university after ten years as a student if medieval history — for there was a great historian there at that time Ernst Kantorowicz – who in turn had been a young acolyte of the poetic circle of George.

On the other hand, I was able to receive “medieval” scenes because I had to imagine them. I had only the knowledge of the medieval that was in my surroundings.

Yet “medieval” by some instinct for home too, as your grasslands are to you — however actual they were — imaginary. As the demand your imagination to be satistied. I still am aroused by the medieval — by the actual documents I’ve come to know in study, but also by the romance and fairy tale that I’ve known since earliest childhood. As “Africa” is another realm that I come alive to. And the sea-shore.

I’ve tried to “get” San Francisco, the city — and I’ve no sense of it (as I have no sense or feeling for political ideals in the poem) — so: there are areas of our thought and feeling the poet doesn’t take hold in.

Thinking of your plans to leave Harvard — if you could manage it — Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Denise Levertov, Ginsberg — a Canadian Poetess Margaret Avison — and I are all going to be reading, lecturing, conferring etc. in a Simmer Session course at the university of British Columbia at Vancouver July 24th — August 16th, eleven class-meetings 8-10 pm Fee $12.00 It will be a period too tho of many other discussions, for it will be the first time any three of us have been together at the same time same place. And we are all eager for the exchange. for information and enrollment the catalog says apply to: Creative Writing Workshop, Department of University Extension, U. of B.C., Vancouver 8, B.C.

I would be glad to see more poems if you find time to send them— yrs.

Robert Duncan

“Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Lovely to read artists of any discipline communicating so helpfully and freely. Originally mistakenly typed “feely.” Guess it might have worked too.

Great letter, but must point out that K. Irby no right to give you or anyone “permission” to reprint this letter.

The right to grant permission to reprint a letter ALWAYS remain with the letter writer. The person who receives the letter doesn’t get that right simply by having the letter. So it was Robert Duncan’s right, which after death passed to his heirs’ or literary executor, etc. And it’ll stay that way until the copyright expires…

Don’t mean to be anything here other than precise about authorial rights.

This letter is historically important in its reference to Kantorowicz’s influence on Duncan — especially in the framing Duncan wishes to give it with Irby — ‘Medieval’ self-avowedly both ‘heimat’ & ‘eingebungen’ – historically given yet emphatic in its imaginative sourcing — which is true/real/primary? — it must be necessarily imagined as a ‘fairy story’ Duncan says yet then as with ‘Africa’ (the philosophical discard that hid ‘sins’ of empire) as real today as ever it was — all the thresh-holds – indeed sea-shores that were crossed for what purpose — is it mythos over logos or vice versa — ‘no feeling for political’ Duncan writes in ’63 — so what happened soon after with the Vietnam war” — was this an extension of the contradiction — the falling out with Levertov — an avoidance of praxis — too much ‘concrete’ — keep it song-like — non-political — the two bodied ambivalence of a right held intact