Robert Kelly on Brooklyn (3)

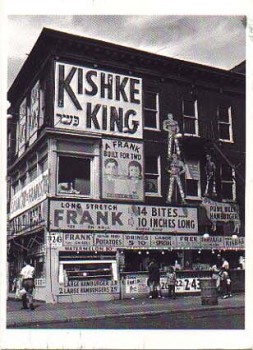

Pitkin Avenue, early 50ies

CITY AS PILGRIMAGE (continued…)

Pitkin Avenue, early 50ies

After the movies, a hot potato knish, square as a stiff cushion, peppery, greasy fingers you could lick after the main dish, a delicate aftertaste. A good cure for memories. A good banishment of sentimentality. Lick the salt, lick the skin. And then go left again, down to the end of Pitkin Avenue.

Hopkinson was an open side street, but most of the side streets off Pitkin were dark with buildings, crowded with tenements. Amboy was notorious for its tough kids in gangs, a book about them, but all of these streets were forbidding by day, downright scary at night. Not that there were bad people; just so many people, the sheer mass of half-imprisoned crowds stifled in railroad flats, five or more to a room. It is a kind of city panic that one feels, the way the ancient Greeks sometimes, at brightest noon, felt sudden terror out in the open – too many trees, too many leaves, too many birds. They called it panic fear, the touch of Pan, the wild otherness that suddenly chills the blood. Here the street might look empty but you could feel them by their thousands inside, the hardworking poor, the exhausted wives and restless children, studying books in more than one language – when any language at all is foreign to a child at bay.

And underneath most of the tenements were basement shops. You went down five or seven iron steps and came into an airless place, a singe naked lightbulb hanging from a tin ceiling, low. The one I remember best was a tailor shop. A hairless man with no shirt, in an old woolen vest gaping open, sat at a sewing machine; his feet kept moving as he pumped the treadle that ran the motor that ran the belt that made the needle go up and down. He had no fingernails. He could hear but could not speak, it seems, and all he did was sew all day and night, taking orders from the tailor we talked to. Who took measurements for my mother’s coat, my confirmation pants. I stood while the tailor’s fingers, he did have nails, probed my thighs and hips and waist to get the measures right. My mother would tell me over and over again every night we were on our way to the tailor, or any merchants, Remember, we’re Jewish, Remember, you’re a little Jewish boy. What did it mean, why did I have to remember it? Anokhi yehudi, I’m a Jew – the words that Disraeli murmured clearly on his deathbed after a lifetime as a practicing Christian Conservative Englishman they told me, every Jew knows that, assert your being with your dying breath, anokhi yehudi, and there I am, plump little boy with fat cheeks and a white shirt too tight around the collar and a red tie and a curvy little nose. Whatever I was, I felt this is where my home was. Pitkin Avenue. The people who talk. Anokhi yehudi.

Pitkin ends at a forking of streets, and aptly at the apex of the fork stood the great garish wonder restaurant, Kishke King. This was the pilgrim’s one auberge along his way. Loud! Greasy! Coarse! Ethnic and shouting and profoundly safe, fluorescent bright, homey, heymish, cheap. Kishke the stuffed small intestines, derma the stuffed big intestines – grilled and sizzling in its own juices. But stuffed with what? Who can say? Chicken fat and matzo meal and carrots I guessed, from consistency, from color. Kishke – you got a coil of it and sliced and ate like andouillette. With derma you got a big thick slice and tore at it with knife and fork. Everybody ate there, and it was the only place that really counted for such food. But they also provided all the traditional deli meats, pastrami and corned beef, steamed brisket streaky with fat, brisket lean but juicy, and kosher frankfurters, called kosher red hots, to be eaten in soft rolls with pale yellow turmericky mustard slathered on it, I never liked their mustard, I liked everything else, and the root beer you drank it down with. Or I did, and the other kids, but the older people drank only seltzer, which, with the faintest affectation, really a kind of delicacy, they called vichy – visshie it sounded like, and never reminded them or me of the Nazi collaborator regime in France.

Pitkin ends at a forking of streets, and aptly at the apex of the fork stood the great garish wonder restaurant, Kishke King. This was the pilgrim’s one auberge along his way. Loud! Greasy! Coarse! Ethnic and shouting and profoundly safe, fluorescent bright, homey, heymish, cheap. Kishke the stuffed small intestines, derma the stuffed big intestines – grilled and sizzling in its own juices. But stuffed with what? Who can say? Chicken fat and matzo meal and carrots I guessed, from consistency, from color. Kishke – you got a coil of it and sliced and ate like andouillette. With derma you got a big thick slice and tore at it with knife and fork. Everybody ate there, and it was the only place that really counted for such food. But they also provided all the traditional deli meats, pastrami and corned beef, steamed brisket streaky with fat, brisket lean but juicy, and kosher frankfurters, called kosher red hots, to be eaten in soft rolls with pale yellow turmericky mustard slathered on it, I never liked their mustard, I liked everything else, and the root beer you drank it down with. Or I did, and the other kids, but the older people drank only seltzer, which, with the faintest affectation, really a kind of delicacy, they called vichy – visshie it sounded like, and never reminded them or me of the Nazi collaborator regime in France.

After the Kishke King, the streets darkened the way residential streets do; the shops are gone, their quivering neon signs all blue and yellow still shimmer back there when I turn and look out of the back window of the bus – that now moves faster, close to its destination. Utica Avenue. The great crossroad. Where Eastern Parkway begins, the splendidly wide boulevard, grand and gracious as anything Baron Haussman sketched out, four lanes in the middle, lined with two broad leafy medians with benches spaced out among trees, wooden slatted benches on which all of Brownsville and Crown Heights sat out late all spring and summer and fall. The trees hummed all round with the talk, argument, reminiscence – a Homeric sound, like the old men on the walls of Troy, but the sound of business too, deals and contracts and arrangements, people giving vent, singing their aggravations. “Harry, you’re aggravating me.” Beyond each mall ran a one lane street rimmed with parked cars.

On the corner of Utica and Eastern Parkway was the real spiritual homeland of this end of Brooklyn Dubrow’s Cafeteria, the agora of us all, where every Marxist who still could walk, and all the young intellectuals, squinting through our hornrim glasses at the pretty girls we were bold enough to call out fancy literary references for them to overhear, too shy actually to talk to them. Politics and religion, serving God and getting rid of Him, McCarthy and Eisenhower – sitting there watching we talked big, but watched with awe, almost envy, the tough still-young men with rolled-up sleeves that let us see and study their hairy muscular arms marked with blue tattooed numbers from Dachau and Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

(There was another Dubrow’s, on Flatbush Avenue, right near Erasmus Hall High School where the smart kids went, and near Brooklyn College. That Dubrow’s duked it out with Garfield’s on the other side of Church Avenue – and Garfield won by virtue of its spectacular mosaic wall, all colors and nativism and popular front imagery, and glittering in green and gold. And yet another Dubrow’s in Manhattan, in the garment district. The cafeteria as an institution is gone – the Automat, the Waldorf (long the center of Village indecorum and the midnight arts), Bickford’s – and I miss them all, but none more than Dubrow’s – an agora it provided, as well as decent food, bright lights, and tolerant of long sieges of babbling intellectuals at the pale tables.)

(There was another Dubrow’s, on Flatbush Avenue, right near Erasmus Hall High School where the smart kids went, and near Brooklyn College. That Dubrow’s duked it out with Garfield’s on the other side of Church Avenue – and Garfield won by virtue of its spectacular mosaic wall, all colors and nativism and popular front imagery, and glittering in green and gold. And yet another Dubrow’s in Manhattan, in the garment district. The cafeteria as an institution is gone – the Automat, the Waldorf (long the center of Village indecorum and the midnight arts), Bickford’s – and I miss them all, but none more than Dubrow’s – an agora it provided, as well as decent food, bright lights, and tolerant of long sieges of babbling intellectuals at the pale tables.)

One long block west along Eastern Parkway I finally came to the library, full of books on social theory and psychology that I was deep into in those days. But to remind me of my other, older, inner nature there was on the wall of the main staircase, so I had to see it every time I climbed up to humanities section, a sepia reproduction of a painting of a life-sized Sir Galahad, rapt in contemplation of what only he could see. Sometimes I mocked as I stepped up. Sometimes I was ashamed, and wanted to see it too.

The street corner outside Dubrow’s , where the bus ended and began, was well-lit by the big shining letters of Dubrow’s sign, right by the kiosked entrance to the IRT subway (the letters stood for Interborough Rapid Transit, but only pedantic little kids like me every remembered that). Right next to the entrance was the big news stand, to which people came from a mile or more around at ten-thirty or eleven every night to get next morning’s New York Times. One autumn night half a dozen people and I stood around among the shifting yellow leaves and talked with young John F. Kennedy, then campaigning gently, even refinedly, through overwhelmingly Democratic Brooklyn. The man glowed. With his brown hair and the candid intensity of his face, he had an aura I’ve never seen in any other human. Not an aura of power, not at all. He had little power, and little effect in government, as it turns out. But an aura anyhow – was it fate? Was it Eros? Whatever it was, maybe the Elf–shine the Old English called what we call beauty, he had it, and it made his presence absolute. He didn’t have much to say, he listened, he smiled, and what he said was spoken from inside that presence, and had not much to do with the usual deployment and reception of words. Phatic, the linguists might call it, speech that tells you only I am here and you are here, we are together in this world. And maybe that is enough for words to say.

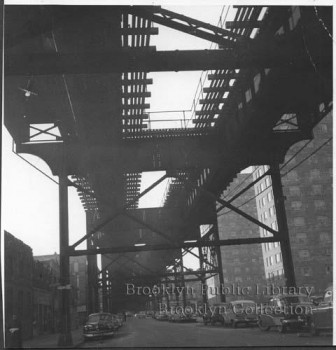

IRT on Livonia

North: Cemeteries and Kierkegaard

If I cross Crescent Street the way I did whenever I would, several times a week, I would set off on my pilgrimage east to the book, but this time instead just stand there on the northeast corner of Crescent and Belmont, my back to the vacant lot with that strange deep declivity in it, weed and dirt, where we could sled down twenty or thirty feet in winter, now stand and wait, and wait, the B-13 bus would come along for me. I would be able to see it coming from blocks away, trundling up the largely empty Crescent Street from the real emptiness south of us along Jamaica Bay, to which I would also at the proper time be journeying, in search of what only emptiness can give.

But you have to understand the heat of Crescent Street. Hot enough so a fig tree grew in one back yard, like the peach tree in ours. Hot with a gentle, pleasant heat I have only felt anywhere else in Italy, in the marshy fields of the Veneto, the little mainland towns back of Mestre, on the way to Venice. Crescent Street, I then understood, years later, felt the way it did because Italians brought their weather here with them. A microclimate, an empty street shimmering asphalt between vacant lots.

So when the bus comes it takes me up this Crescent Street, my long walk to Conduit Street and Sunrise Highway and Liberty Avenue all crammed into two minutes of jolting bus. And then the streets I less often walk, from Liberty up past little streets, Italian streets, passing old Buonfiglio the tailor, who made me my Confirmation jacket, two-tone, fawn and beige, soft cashmere, we were never Italians, the bus kept going, stopped at the long light at Atlantic Avenue, the wide busy street and the only one that stretched from one side of Brooklyn (the freighter docks in Arab and Kurdish Red Hook) to the other (mild Catholic white Woodhaven in Queens). Then one long block to Fulton Street, another very long Brooklyn street, this one too petering out into Queens, but starting not due west like Atlantic, but angling down from its start right across from the greatest of all islands, at the ramp down which the Manhattan Bridge spilled heavy traffic into our holy borough. Fulton Street bore on its back for miles the elevated trains of the Jamaica line, and just at the point the bus is now, the great elevated structure bends north, and runs above Crescent Street a quarter-mile or so to its turn east at its appointment with Jamaica avenue, along which it will run far out into the commercial center of Queens, where Gertz’s department store brought people (like my mother) even from Brooklyn, and the great Loew’s movie palace was Moorish and gold.

But the bus wanted none of that. It turned left on Jamaica, went a few blocks and turned right again, and immediately entered a holy land, a land apart. Now the bus began to climb a narrow houseless crowded street up the terminal moraine left by the last glacier – a vast geological remnant that stretches from Brooklyn Heights and Fort Greene Park all the way through Brooklyn and Queens, dives under the sea into Long Island Sound, surfaces a hundred miles later as Cuttyhunk and the Elizabeth Islands, then Cape Cod, then Charles Olson’s Cape Ann, before it vanishes for good in the ocean. In this part of Brooklyn the moraine is called Cypress Hills, our cemetery ridge, cypress (the actual tree does not grow in cold New York) from its association with cemeteries. For here the graveyards are, Jewish, Christian, common. Squeezed between fields of monuments and gravestones that stretch west and east as far as the eye can see, the little street called by the name of the hills climbs steeply. The bus climbs, and I am in heaven. This is my sainte-terre, my terrifying magic place through which I would never dare walk alone at night, but in the daytime, in the diesel perfume of the little squat bus, in chatter of engine and rattle of newspapers of the passengers, I can feel the utter ecstasy. This place is literature. This is the land of symbols. Blind angels with stone bedsheets draped over the invisible dead. Shrouded urns on Jewish tombs. Here were the people who had gone before, and who were now, if they were at all, in some condition where they knew the answers to the questions that worried me and all the living.

But here was not the place for questions. Here was the thrill of understanding something enclosed by the city but that was not the city. This place, with the Empire State Building clear in the not great distance when we reached the top of the ridge and tilted down into more cemeteries, more grey stone and personless avenues, this place was further away from New York than the pine woods of Pennsylvania or the mountains of Greene County where I spent a summer around his time of my life and got bitten by a copperhead. This place was further than a snake, further than a mountain. Because this was the eternal landscape of the book, of the Bible, of death and dream – all present here around me safe on the bus. When I came by at night I could see the hound of the Baskervilles if I chose, or the demoness (really a goddess) Lilith flitting naked pale among the tombs. In the daytime I was in Rome or Athens, these funny Greekish sarcophaguses and miniature mausoleums had the scale of antiquity all jostled wrong. Nothing was the right size.

But here was not the place for questions. Here was the thrill of understanding something enclosed by the city but that was not the city. This place, with the Empire State Building clear in the not great distance when we reached the top of the ridge and tilted down into more cemeteries, more grey stone and personless avenues, this place was further away from New York than the pine woods of Pennsylvania or the mountains of Greene County where I spent a summer around his time of my life and got bitten by a copperhead. This place was further than a snake, further than a mountain. Because this was the eternal landscape of the book, of the Bible, of death and dream – all present here around me safe on the bus. When I came by at night I could see the hound of the Baskervilles if I chose, or the demoness (really a goddess) Lilith flitting naked pale among the tombs. In the daytime I was in Rome or Athens, these funny Greekish sarcophaguses and miniature mausoleums had the scale of antiquity all jostled wrong. Nothing was the right size.

Really, it was and is a very curious zone, this ridge through the whole borough; how odd to make the highest land in the city into a necropolis, where the dead, who have no eyes, have the best vistas in all New York. Instead the dead are conspicuously housed in great stone markers with cubes and pyramids and spires, to be looked up at by the living. When I was a child, it made me feel that dying was the entry to some world of wealth and power, solidity and grace and dignity. No hint of worm or rot, just big stone geometries to live quiet in. Quiet as a book. Quiet as a child living in his imagination. When I read Poe and Lovecraft, of course their graveyards were here, my own. But when I read Malory or Wolfram, these phony classical buildings felt like the Roman ruins on which the great Grail legends had been built in the Middle Ages. All fiction grows out of rubble, as these imposing almost-empty edifices rose out of death. And death’s sinister partner, Fama, the lust for reputation, for admirers in posterity, for a name to come.

I couldn’t read them from the bus, hence could not know the names on these gaunt sepulchers, so in that sense they failed in their design. I could not name, let alone revere or revile the beings inside them. But they in turn, those strange buildings, could inhabit my mind. So this drive over Cemetery Ridge into Ridgewood was the delight of the week. Sometimes I’d go with the family in my father’s car on our shopping trip to the German butcher and the big A&P on Fresh Pond Road. But I liked best being alone, on the bus, where I sat much higher up (we always said ‘high up’ in Brooklyn) than in a car, and I could see far off into the fields of the dead, and imagine I was staring into Lyonesse or fairyland or some fool thing that would not have let me come in anyway. But Brooklyn was always a great place to look away from – it gave you all the differences and sullen dogged presence you needed in you, around you, to free you to look up and see far off the other country, the Ailleurs of Michaux and Borges and Blackwood.

And here something like that came about me. After the cemeteries the level plain again, Ridgewood and Maspeth blurring out over the fields east into Queens, west along Myrtle Avenue back to Brooklyn. I had come from Italy and from the land of the Jews, and was coming now into Germany. Here the pork butchers, any many a dark beer saloon, and the cheese shop under the el where I could buy my favorite cheap Finnish gruyere, nuttier and sweeter than the real Swiss I wouldn’t get to taste for years. Cheese and pork and bakers. And under the el too Ridgewood Grove – a grove it might once have been, now a squalid small-town arena for wrestling matches when wrestling had just come into fashion, after World War II, when we had bodies again, and we could slam them around on the canvas or slap them around in the ring or, roller derby girls, on the rink. Our bodies came back and we watched the bodies of others to understand our own—Antonino Rocca, Lord Carlton, Gorgeous George, the strutting muscular characters, none too young, who taught us the thrill of pretending, of mock blood and real gravity, and made us hope that we too, when we had reached a certain age, would have muscular presence, and a smile on our haughty faces as fate slammed us down the third time. Wrestling suited the mood of that day, after the war, when we still needed to fight, but no longer needed to kill.

But out from under the el on Palmetto Street, out into the open on Fresh Pond Road, through the airy northern feel of Ridgewood, you could walk a long ways, up towards the Passionist monastery, whose priests wore a white heart and cross stitched on their cassocks, along with signs I don’t remember, that may have been words. One of the priests took an interest in me I felt grateful for but did not understand. I understood nothing but streets and shadows, the shapes of houses, the intimate landscapes of pages of the books. How this very street seemed to open out towards Metropolitan Avenue and the broad plain north of the ridge, a plain also filled with the dead, the endless rolling fields of Calvary (the Long Island Expressway runs past it now) and Saint John’s cemeteries, where my own family was buried. There was an obscure rivalry, too strong a word, but what a child felt as a difference-with-pressure built into it, between the branch buried in Calvary and the branch buried in Saint John’s.

(to be continued)

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Simply brilliant

I’m afraid you’ve gotten a few of your facts mixed up. There was never a Dubrow’s on Flatbush Avenue – perhaps you are thinking of a Concord caterer/cafeteria. Also the photo you show should be credited as the Dubrow’s on Kings Highway.

When it comes to the legendary, sorely missed old NYC cafeterias, I’ve gathered almost all the archival photos, video and facts available for a documentary film and, possibly, a book.

New finds are always welcome, though.

Here’s RK’s response to Marcia (which he emailed her directly & cc’d me who suggested we put it here in the res publica space): “Pierre Joris passed along your kind corrective. You’re perfectly right — the cafeterias on Flatbush were the Concord (as you say) and the rather more opulent Garfield. I loved them both, the former for the food, the latter for the ambience. My aunt lived not far away, but I came to the cafeterias because most of the would-be wild teenage writers and artists hung out there, at least those in Flatbush. (Influence of Erasmus next door, and Bklyn College not all that far away.) Closer to my home was the great Dubrow’s on Eastern Parkway at Utica Avenue — the greatest single home of hot talk and political palaver this side of Zurich. My love of that place renamed the Garfield — sorry!

There was a Dubrows on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan — not part of my story, though my own first job was in the garment district.

The pictures — I didn’t choose them or even know about them before Pierre bravely found and mounted them. The Dubrows shown is I think the one on Coney Island Avenue near Kings Hwy, but I’m not sure — not part of my pilgrimage.”

ps. the pictures all come from that great online treasure trove, aka the Brooklyn Public Library.

I don’t believe I’m mistaken but I seem to

remember a Dubrow’s Restaurant on Avenue M

and East 16th St. Brooklyn NY.

I got taken to this site when searching for a pic of Garfields Cafeteria. That picture is Dubrows, which was absolutely on Kings Highway and E. 17th St. There was also another one on Eastern Parkway. Garfields was on Flatbush & Church.

Matt:

That Dubrows was on the corner of Eastern Parkway and Utica. We lived @ 1074 Eastern P’kway and 914 Montgomery St. from 1951-1956. Went to PS 221,(1944) Erasmus Hall HS,class of June 1950 and Brooklyn College (class of 1954)