Eric Mottram on Triggernometry (5)

So Nomadics will ring the year out with the final installment of EM’s essay “The Persuasive Lips.” Apologies for leaving the footnotes in a mess, but I simply don’t have the time to reformat these right now. Tomorrow will be another day, we hope.

So Nomadics will ring the year out with the final installment of EM’s essay “The Persuasive Lips.” Apologies for leaving the footnotes in a mess, but I simply don’t have the time to reformat these right now. Tomorrow will be another day, we hope.

V

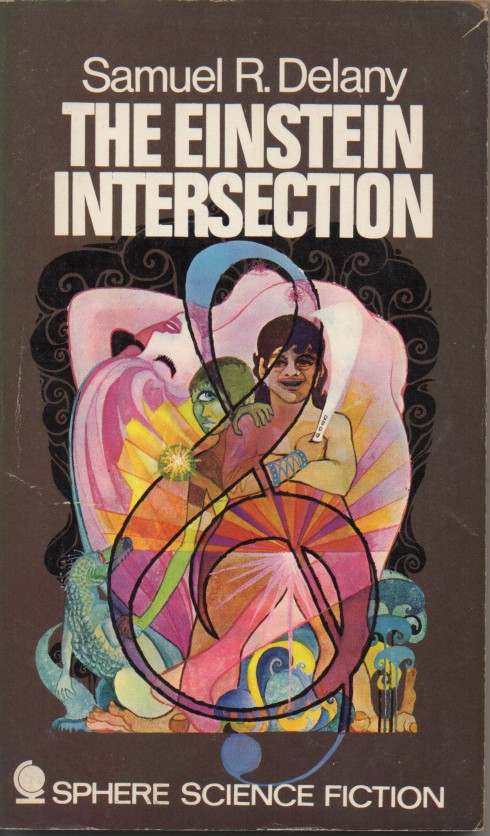

Samuel R. Delany understands more of the myth in his novel The Einsten Intersection (1968), where Billy the Kid appears as a redheaded boy with gold lashes and transparent skin whose eyes ‘had no whites, only glittering gold and brown … dog’s eyes in a human face: “My mother called me Bonny William,” the Kid announces. “Now they all call me Kid Death.” ‘66 Asked why he kills, he replies: “I am more different than any of you. You scare me, and when I’m frightened” – laughing again – “I kill.” He blinked. “You’re not looking for me, you know. I’m looking for you.” ‘ Kid Death is ‘a criminal genius, psychotic, and a totally different creature,’ something that was apparent from his tenth year. As a man, he is tied up with what he calls ‘their past,’ the past of the human race in the West. He is an object other men wish to kill – as if death could be killed, or the impulse to kill could be killed, or ended by killing. He stands at the centre of impotence in western culture. The only figure immune from Kid Death is Green-eye, Delany’s image of the Green Man. He is a salvation figure of love ‘chary of ritual observances,’ and as one character says: ‘Everybody blames the business on his parthogenetic birth.’ According to Lobey, the narrator-hero of the book, Kid Death seems to be sixteen or seventeen or ‘maybe a baby-faced twenty,’ although ‘his skin was wrinkled at the wrists, neck, and under his arms.’ Lobey first asks what the westerns he himself really admires are, and then what a western is. He replies: ‘It’s an art-form the Old Race, the humans, had before we came.’ Within that repetition, Kid Death is himself a killer repetition factor that has to be transcended, not killed. When he tempts Green-eye, it is through the repetitions of old forms of power, old ideas, old technology; insane recoveries of exhausting and exhausted actions and ideologies.’ “There,” said Kid Death, “there are the deeds and doings of all the men and women and androgynes on this world to remember the wisdom of the old ones. I can hand you the wealth produced by the hands of them all.” Green-eye’s green eye widened. “I can guarantee it. You know I can. All you have to do is join me.”

Green-eye refuses the familiar offer to turn ‘rock into something to eat,’ to accept the luxury of power, to ‘turn this mountain-top into a place worthy of you.’ Kid Death brings on his thunder but finally makes his getaway: ‘Needle teeth snagged the thunder that erupted from behind the mountains as he threw back his head in doomed laughter. Naked on his dragon, he waved a black and silver hat over his head. Two ancient guns hung holstered at his hips, with milky handles glimmering.’

The next section of the book begins with a conversation between the author and Gregory Corso: ‘Jean Harlow? Christ, Orpheus, Billy the Kid, those three I can understand. But What’s a young spade writer like you doing all caught up with the great White Bitch?! Of course I guess it’s pretty obvious.’

Then Kid Death appears saying ‘Howdy, pardners’ – ‘Where flame slapped his wet skin, steam curled away.’ He vanishes into ‘wherever he goes.’ The next section opens with part of the author’s journal, written from Mykonos in December 1965 and concerned with his need to ‘excise … the images of youth’ which plague him – Chatterton, Greenburg, Radiguet; ‘By the end of TEI I hope to have excised them. Billy the Kid is the last to go. He staggers through this abstracted novel like one of the |l|S^d children in Crete’s hills.’

The plot of the hero-narrator, Lobey, is to hunt down Kid Death, since he is the only figure for whom the Kid is not paralyzing. Lobey is the Orpheus of the book, his flute a twenty-holed machete. He is a figure of difference whose difference is not destructive, part of the motion of change leading away from destructive myths and their rigidification of our lives. The traditional figure of law and order, the sheriff agency, is called Spider, a man of strength who is, however, himself caught in unimaginative procedures against death or the statification of men. He defines his job as a limited quest:

‘ “it demands you take journeys, defines your stopping and starting points, can propel you with love and hate, even to seek death for Kid Death -“

“- or make me make music,” I finished for him.’

But Spider may acknowledge this double venture, against creative imagination and against destructive myth, only within the fixed content of his continuing problem; speaking, as it were, from the future of the book, he says:

Wars and chaoses and paradoxes ago, two mathematicians between them ended an age and began another for our hosts, our ghosts called Man. One was Einstein, who with his Theory of Relativity defined the limits of man’s perception by expressing mathematically just how far the condition of the observer influences the thing he perceives. . . . The other was Godel, a contemporary of Einstein, who was the first to bring back a mathematically precise statement about the vaster realm beyond the limits Einstein had defined: In any closed mathematical system -you may read ‘the real world with its immutable laws of logic’ –there are an infinite number of true theorems – you may read ‘perceivable, measurable phenomena’ – which, though contained in the original system, can not be deduced from it – read ‘proven with ordinary or extraordinary logic’… At the point of intersection, humanity was able to reach the limits of the known universe with ships and projection forces that are still available to anyone who wants to use them -‘

But Lobey’s search takes him to the source cave of all earth caves – that is, to the chthonic teleology within the history of mythology. The source cave turns out to be ‘a net of caves that wanders beneath most of the planet. . . . The lower levels contain the source of the radiation by which the villages, when their populations become too stagnant, can set up a controlled random jumbling of genes and chromosomes.’ Mythology consists of the forms that source energy takes: Lobey is Ringo as well as Orpheus, and Spider is Pat Garrett and Iscariot. Lobey carries a two-edged singing knife. The Kid needs both Orpheus and Garrett because, although he can change things, he cannot make something out of nothing. As Spider tells Lobey:

He cannot create something from nothing. He cannot take this skull and leave a vacuum. Green-eye can. And that is why the Kid needs Green-eye…. The other thing he needs is music…. He needs order. He needs patterning, relation, the knowledge that comes when six notes predict a seventh, when three notes beat against one another and define a mode, a melody defines a scale. Music is the pure language of temporal and co-temporal relation. He knows nothing of this, Lobey. Kid Death can control, but he cannot create, which is why he needs Green-eye. He can control, but he cannot order… that is why he needs you.

The final section contains William H. Bonney’s letter to Governer Wallace, telling him that he would emerge to give ‘the {desired information’ but is afraid of his enemies. But in this book the Kid, through Spider, has Green-eye strung up. Lobey plays his music and Spider whips the Kid; a flower devours his body. Lobey’s music also enables Green-eye’s death. The myths are ‘ excised and the conclusion is open:

‘ “It’s not going to be what you expect.” [Spider] grinned, then

turned away.

“It’s going to be . . . different?”

He kept walking down the sand . . .’

At least Billy the Kid has been recognized as deadly, a deathly creation of men at a particular time and in a particular place, usable only if those circumstances are made to repeat themselves. There is in Delany’s book no question of endless archetypes being divorced from cultures so that they may be perpetuated as images of survival. The cave source can produce only what men wish to need. And certainly a Black American should not need white killer myths.

The gunfighter lived a life of repetitive style dependent on a repeating weapon, the revolver – an ideal, if malignant, way trough the problems of both law and stability, creativity and risk. In traditional kung-fu and akaido, at least some training of the whole body-mind is required through apprenticeship and dedication. Henry Fonda may look like a teacher in The Tin Star (1957) but he is not. He trains for a simple synchronicity of eye, muscle, and repeater, which is to permit his young pupil – a trainee sheriff – manhood. As Walt Whitman wrote bitterly in his 1856 poem ‘Respondez!’: ‘Let them sleep armed! let none believe in good will!’ But armed lack of good will is a response to thinness of opportunity in the latter-day West – and it obviously is in Peckinpah’s movie.

In Pinon Country (1941), Haniel Long tells how two young men from New York attempted to hold up ‘The Apache,’ South Pacific No. 11, near Las Cruces, New Mexico, in 1937.67 They were battered by the passengers and sentenced to serve from fifty to seventy-five years on pleading guilty to second degree murder (a man had been killed). One of the men, Henry Lorenz, had been born in a detention camp in Germany, after his family returned from a failure to settle on a farm colony in Russia. After the mother died, the family emigrated. The father remarried. The stepmother disliked Henry, who took to being ‘crazy about the West’ and spent his money on western magazines and movies. He ran away from home and tried to save money working in a New York shoe store. When he had accumulated 500 dollars, he invited Harry Dwyer to join him ‘to go West and be cowboys.’ (Dwyer was of French-Irish descent, and had also been born abroad). Their money ran out on girls, so they held up the train. Just outside the site of their trial, at Old Mesilla, was the Billy the Kid Museum containing the Kid’s leg-irons and one of his guns. From the Lincoln County Billy the Kid Museum (housed in the old jail), Haniel Long sent the curator a newspaper cutting of the Las Cruces trial, and suggested ‘a museum file under the heading “Results of Hero-Worshipping William Bonney”: it is the old story of two eastern boys who wanted to play Billy the Kid.’

VI

Non-violence is related in urban competitive society to inadequate manhood. In an essay entitled ‘the Science of Nonviolence,’ John Paul Scott begins by pointing out that in Hopi Indian society even the thought of violence is considered wrong, and few weapons are available. A violent man is seen as deranged and people get out of his way. In white society, the damage caused by deranged men is also limited by the availability of /Weapons. As the earlier part of the present essay noted, most homicides in America are committed with handguns in the 1 hands of people who are not habitual criminals, but who are I* acting on impulse during quarrels with relatives and friends. Social disorganization among men and animals is a major cause |of destructive violence. As John Paul Scott says, ‘the principle of multiple causation always holds, and some will escape.’68 We need to investigate multiple causation, the intersection points of, pfor example, lack of opportunity, sexual unfulfilment within or ‘Outside the family, immigration disruptions, divorce, the boom fmd depression cycles of capitalism, and the nature of constructively enjoyable behaviour as a counter to other forms of power. Poor pay for a meaningless and menial job, itself at the mercy of [economic change, permits the violence of leisure compensations in the form of instant dominance. Personal power, with an easily ed gun, may shift rapidly into the impersonal scale of ffwar. In fact, under any totalitarian system we are expected to K become a soldier or worker or consumer at the next command of ^authority.

In ‘The Triggered, the Obsessed and the Schemers,’ Jean Davison reports the results of experiments designed to uncover possible reasons for TV-inspired crimes, mainly research into the cues that trigger attack. She quotes Dr. Robert M. Liebert, a child psychologist and a principal investigator for the Surgeon General’s enquiry into TV and social behaviour, who believes that exposure to constant TV violence in the home leads to ‘an acceptance of aggression as a mode of behaviour.’ He adds: Even perfectly normal children will imitate antisocial behaviour they see on television, not out of malice but out of curiosity.’ Such exposure is also believed to contribute to bystanders’ failure to respond to a victim’s need for help, to imitation of TV behaviour, and to the use of TV as a textbook of violent methods. The evidence appears to be overwhelming.69 In The Einstein Intersection, Delany attacks the perpetuation of myths encoding these permissions and intersections, which reach so far down that they are considered to be natural, becoming, as Herbert Marcuse proposes in An Essay on Liberation, second nature:

Self-determination, the autonomy of the individual, asserts itself in the right to race his automobile, to handle his power tools, to buy a gun, to communicate to mass audiences his opinion, no matter how ignorant, how aggressive. Organized capitalism has sublimated and turned to socially – productive use frustration and primary aggressiveness on an unprecedented scale -unprecedented not in terms of the quantity of violence but rather in terms of its capacity to produce long-range contentment and satisfaction, to reproduce the ‘voluntary servitude.’ . . . The established values become the people’s own values: adaptation turns into sponteneity, autonomy; and the choice between social necessities appears as freedom.70

It is a degeneration of social value of this kind that we observe in the relationships between guns and culture, which this essay has tried to suggest a way of understanding.

* * *

We live on the whims of men in custom-tailored suits, who ride in black limousines and whose addition to human insight and knowledge would hardly challenge Billy the Kid.

Walter Lowenfels Loving You in the Fallout

Unless everyone in America owns a handgun there will never be peace in this country [for] no country in the world offers its citizens a greater choice of guns than the United States…. We are blessed because anyone in America can have the gun of his choice at a price he can afford. For those who are on relief and unemployed the government could supply surplus weapons from the armed forces at the same time they give out food stamps and unemployment cheques.

There is absolutely no reason why everyone in this country could not be armed by 1973.

Art Buchwald Washington Post 23 May 1972

Billy the Kid said: ‘Quien es?’ Pat Garrett killed him. Jesse James said: ‘That picture’s awful dusty.’ He got on the chair to dust off the death of Stonewall Jackson. Bob Ford killed him. Dutch Schultz said: ‘I want to pay. Let them leave me alone.’ He died two hours later without saying anything else.

William Burroughs The Wild Boys 1976

Notes

- Tim Findlay, ‘The Revolution Was Televised,’ Rolling Stone, 20 June 1974, pp. 6-8.

- Caryl Rivers, ‘The Vertigo of Homecoming,’ The Nation, 17 December 1973, pp. 646-9.

- Thomas McGuane, The Bushwhacked Piano (New York, 1973), p. 138. See also Larry McMurtry./fZ/Afy Friends Are Going to be Strangers (1972; New York, 1973), pp. 8-9.

- E.L. Doctorow, The Book of Daniel (New York, 1972), p. 84.

- Louise Thorensen, with E.M. Nathanson, // Gave Everybody Something To Do (New York, 1974).

- Eric Norden, ‘The Paramilitary Right,’ Playboy (June, 1969).

- ‘Alcoholism: New Victims, New Treatment,’ Time, 4 April 1974.

- ‘Domestic Disarmament,’ The Nation, 23 February, 1974; ‘Gun Crazy,’ The Nation, 1 March 1975; ‘The Baltimore Gun Bounty,’ The Nation, 5 October 1974.

- Richard Hofstadter and Michael Wallace (eds), American Violence: A Documentary History (New York, 1970), pp. 24-5.10Michael Harrington, ‘The Politics of Gun Conrol,’ TheNation, 12 January 1974.

- Perry Miller, The Life ofthe Mind in America. From the Revolution to the Civil War (New York, 1965), pp. 240, 248, 264.

- Dixon Wecter, The Hero in America (Ann Arbor, 1941), pp. 352-3.

- Odie B. Faulk, Tombstone: Myth and Reality (New York, 1972).

- Hofstadter and Wallace (eds), pp. 401-3.

- Robert Sherrill, The Saturday Night Special (New York, 1973), p. 3.

- Karl Marx, The Grundrisse, ed. and trans. David McLellan (New York, 1972), p. 45.

17. T.K. Deny and T.I. Williams, A Short History of Technology (Oxford, 1960), pp. 48ff.

- Friedrich Engels, Anti-Duhring (1877-8), II, iii, ‘Theory of Violence.’

- Sherrill, p. 4.

- Sherrill, p. 17.

- S. Lilley, Men, Machines and History, rev. ed. (London, 1965), p. 66.

- Melvin Kranzberg and Carroll W. Pursell, Technology in Western Civilization, Volume 1 (New York, 1967), p. 493.

- Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command (New York, 1948), pp. 49-50.

- W.H.G. Armytage, A Social History of Engineering, 3rd ed. (London, 1961), pp. 49-59, 128, 156, 160, 183.

25. Armytage, p. 160.

26. Roger Burlinghame, Machines That Built America (New York, 1965), pp. 83ff.

27. Kranzberg and Pursell, p. 494.

28. P. Wahl and D.R. Toppell, The Galling Gun (London, 1966); Carl P. Russell, Firearms, Traps and Tools of the Mountain Men (New York, 1968).

29. Tom Hayden, ‘Vietnam, One Year After,’ Rolling Stone, 28 February 1974, p. 6.

30. Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York, 1934), p. 165.

3l. Kranzberg and Pursell, p. 498. 1,

32. Giedion, p. 21.

33. Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Plains (New York, 1931), p. 244.

34. Charles Olson, A Bibliography on America for Ed Dorn (San Francisco, 1965), p. 5; Webb, pp. 244-9.

35. John A. Hawgood, The American West (London, 1967), pp. 284-95.

Raymond Lee, Fit for the Chase: Cars and the Movies (New York, 1969), p. 14.

- Hawgood, p. 295.

- Orrin E. Klapp, Heroes, Villains and Fools (New Jersey, 1962), pp. 27ff.

- David Riesman et. al., The Lonely Crowd (New York, 1950).

- H.B. Sell and V. Weybright, Buffalo Bill and the Wild West (Oxford, 1955; New York, 1959).

- Wecter, pp. 341-63; Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land (New York, 1950), pp. 113-25.

- Ron Chernow, ‘John Ford: The Last Frontiersman,’ Ramparts, April 1974, p. 48.

- B.A. Botkin (ed), A Treasury of American Folklore (New York, 1944), p. 108.

- Eugene Cunningham, Triggemometry (New York, 1941; London, 1967), p.

- Peter G\dz\,Andy Warhol: Films and Paintings (London, 1971), p. 130.

- Wilfred Mellers, Music in a New Found Land (London, 1964), p. 88.

- K.L. Steckmesser, The Western Hero in History and Legend (Oklahoma, 1965), p. 5, n. 3.

- Jim Kitses, Horizons West (London, 1969), p. 8.

- David Lavender, The Penguin Book of the American West (London, 1969), p. 406; Wecter, p. 349.

- Lavender, p. 359; Wecter, p. 349.

- J.D. Horan and P. Sann, Pictorial History of the Wild West (New York, 1954), pp. 57ff; Wecter, passim.

- cf. Charles A. Siringo./f Texas Cowboy (Chicago, 1886).

- Steckmesser, p. 60.

- Horan and Sann, p. 59.

- Steckmesser, p. 68.

- Cunningham, p. 17.

- B.A. Botkin’sy4 Treasury of American Folklore prints parts of Walter Noble Burns’ Saga, The Cowboys Career (St. Louis, 1881), by ‘One of the Kids,’ Siringo’s History of Billy the Kid, (n.p., 1920), and ‘Song of Billy the Kid’ -‘Way out in New Mexico long, long ago, / When a man’s only chance was his own forty four . . .’).

- Horan and Sann, p. 58.

- Steckmesser, p. 84.

- Michael McClure, The Mammals (San Francisco, 1972); The Beard (New York, 1965); Star (New York, 1970).

- Charles Olson, Human Universe and Other Essays (San Francisco, 1965), pp. 139-40.

- Louis Zukovsky, All – The Collected Short Poems, 1956-64 (London, 1967), pp. 49-51.

- Edward Dorn, Gunslinger, Book I (Los Angeles, 1968), Book II (Los Angeles, 1969), Book III (Massachusetts, 1972); Gunslinger 1 and 2 (London, 1973); Michael Ondaatje, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (Toronto, 1970; London, 1981), pp. 28, 43. Poe was president of the National Bank of Roswell, New Mexico.

- Robert Warshow, The Immediate Experience (New York, 1962), pp. 89-105.

- Eric Mottram, William Burroughs: The Algebra of Need (Buffalo, N.Y., 1971), p. 26.

- Quotations in the following section are taken from Samuel R. Delany, The Einstein Intersection (1968; London, 1970), pp. 63ff., 87ff., 96, 101, 120, 122, 131, 136, 159.

- Haniel Long, If He Can Make Her So (Pittsburg, 1968), pp. 45-49.

- John Paul Scott, ‘The Science of Nonviolence,’ The Nation, 26 February 1973.

- Jean Davison, ‘The Triggered, the Obsessed and the Schemers,’ TV Guide [New York], 2 February 1974.

- 70. Herbert Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation (London, 1969), p. 22.

Journal of American Studies, 10, 1 (1976), 53-84.

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Tomorrow will be another day, we hope.”

Tomorrow and 364 more, at least!

Good to be reminded of Eric Mottram’s enthusiasm.