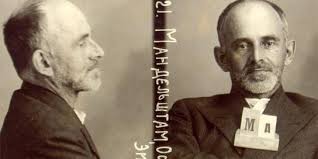

75 Years Ago Osip Mandelstam died

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam — О́сип Эми́льевич Мандельшта́м — was born January 15 1891 & died 75 years ago today on December 27, 1938 in Siberia at a transit camp to the Gulag where Stalin had sent him for writing poems that insulted the dictator. Probably the greatest Russian lyric poet & essayist of the first part of the 20C. I am still awaiting a really great translation into English of the poetry. Many have tried, with variable results: there are several decent versions, but also a number that sound flat or dated (but Mandelstam is a tough tough poet to translate), & a few good ones indeed (I can’t wait for the day when John High’s complete versions will finally come out.) Meanwhile you can read a gathering of Mandelstam’s poems in various new translations online as an Ugly Duckling e-booklet here.

The video above, recorded a few years ago by Nicole Peyrafitte, has Charles Bernstein & me reading extracts from Paul Celan’s radio play on Osip Mandelstam. The text is extracted from my translation of Paul Celan: The Meridian: Final Version — Drafts — Materials published by Stanford University Press; the sections of the play below I posted a few years back on this blog, & reproduce today to honor & celebrate this great poet:

Toward the end of the Meridian Variorum edition the editors reprint a radio play Paul Celan wrote the same year he composed the acceptance speech for the Büchner prize. It is made up of two alternating voices telling an abbreviated version of Mandelstam’s life and a number of Mandelstam poems in Celan’s German translation. I have no Russian & have retranslated these poems directly from Celan’s German versions, without referring to any extent English translations from the Russian (unless some of the Englished versions I read over the years still ghost my memory, a possibility I cannot exclude). Here, a few extracts: first, the speakers discussing Mandelstam’s poetics, and then, one — rather well-known — poem:

1. Speaker: These poems are the poems of someone who is perceptive and attentive, someone turned toward what becomes visible, someone addressing and questioning; these poems are a conversation. In the space of this conversation the addressed constitutes itself, becomes present, gathers itself around the I that addresses and names it.But the addressed, through naming, as it were, becomes a you, brings its otherness and strangeness into this present. Yet even in the here and now of the poem, even in this immediacy and nearness it lets its distance have its say too, it guards what is most its own: its time. 2. Speaker: It is this tension of the times, between its own and the foreign, which lends that pained-mute vibrato to a Mandelstam poem by which we recognize it.(This vibrato is everywhere: in the interval between the words and the stanza, in the „courtyards” where rhymes and assonances stand, in the punctuation.All this has semantic relevance.) Things come together, yet even in this togetherness the question of their Wherefrom and Whereto resounds – a question that “remains open,” that “does not come to any conclusion,” and points to the open and cathexable, into the empty and the free. 1. Speaker: This question is realized not only in the “thematics” of the poems; it also – and that’s why it becomes a “theme” – takes on shape in the language: the word – the name! – shows a preference for noun-forms, the adjective becomes rare, the “infinitives,” the nominal forms of the verb dominate: the poem remains open to time, time can join in, time participates. …..

2. Speaker: A poem from the year 1915:

Insomnia. Homer. Sails, taut.

I read the catalog of ships, did not get far:

The flight of cranes, the young brood’s trail

high above Hellas, once, before time and time again.Like that crane wedge, driven into the most foreign –

The heads, imperial, God’s foam on top, humid –

You hover, you swim – whereto? If Helen wasn’t there,

Acheans, I ask you, what would Troy be worth to you?Homer, the seas, both: love moves it all.

Who do I listen to, who do I hear? See – Homer falls silent.

The sea, with black eloquence beats this shore,

ahead I hear it roar, it found its way here.1. Speaker: In 1922, five years after the October revolution, “Tristia,” Mandelstam’s second volume of poems comes out.

The poet – the man for whom language is everything, origin and fate – is in exile with his language, “among the Scythians.” “He has” – and the whole cycle is tuned to this, the first line of the title poem – “he has learned to take leave – a science”.

Mandelstam, like most Russian poets – like Blok, Bryusov, Bely, Khlebnikov, Mayakovsky, Esenin- welcomed the revolution. His socialism is a socialism with an ethico-religious stamp; it comes via Herzen, Mihkaylovsky, Kropotkin. It is not by chance that in the years before the revolution the poet was involved with the writings of the Chaadaevs, Leontievs, Rozanovs and Gershenzons. Politically he is close to the party of the Left Social Revolutionaries. For him – and this evinces a chiliastic character particular to Russian thought – revolution is the dawn of the other, the uprising of those below, the exaltation of the creature – an upheaval of downright cosmic proportions. It unhinges the world.

2. Speaker:

Let us praise the freedom dawning here

this great, this dawn-year.

Submerged, the great forest of creels

into waternights, as none had been.

Into darkness, deaf and dense you reel,

you, people, you: sun-and-tribunal.The yoke of fate, brothers, sing it

which he who leads the people carries in tears.

The yoke of power and darkenings,

the burden that throws us to the ground.

Who, oh time, has a heart, hears with it, understands:

he hears your ship, time, that founders.There, battle-ready, the phalanx – there, the swallows!

We linked them together, and – you see it:

The sun – invisible. The elements, all

alive, bird-voiced, underway.

The net, the dusk: dense. Nothing glimmers.

The sun – invisible. The earth swims.Well, we’ll try it: turn that rudder around!

It grates, it grinds, you leftists – come on, rip it around!

The earth swims. You men, take courage, once more!

We plough the seas, we break up the seas.

And to think, Lethe, even when your frost pierces us:

To us earth was worth ten heavens.

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024

Poasis II: Selected Poems 2000-2024 “Todesguge/Deathfugue”

“Todesguge/Deathfugue” “Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)”

“Interglacial Narrows (Poems 1915-2021)” “Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello”

“Always the Many, Never the One: Conversations In-between, with Florent Toniello” “Conversations in the Pyrenees”

“Conversations in the Pyrenees” “A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh

“A Voice Full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly.” Edited by Pierre Joris & Peter Cockelbergh “An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press

“An American Suite” (Poems) —Inpatient Press “Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture

“Arabia (not so) Deserta” : Essays on Maghrebi & Mashreqi Writing & Culture “Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012)

“Barzakh” (Poems 2000-2012) “Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots” “The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016

“The Agony of I.B.” — A play. Editions PHI & TNL 2016 “The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans”

“The Book of U / Le livre des cormorans” “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan”

“Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan” “Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones”

“Paul Celan, Microliths They Are, Little Stones” “Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

“Paul Celan: Breathturn into Timestead-The Collected Later Poetry.” Translated & with commentary by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Somebody should translate Ralph Dutli’s German biography of Mandelstam, which is brilliant. And there’s a Russian edition to work with, too, so maybe one needs a translator who can do both German and Russian.

Andrew, indeed — I have the Dutli bio as core to my OM library — it is excellent & should be translated!